As a therapist working with children for over 30 years, I have a collection of pictures of the children with whom I have worked. When I look at the pictures, I proudly and lovingly remember how we worked hard together to achieve their goals: walking, propelling their power wheelchairs, jumping, or simply rolling over to reach for a toy.

I also remember their parents or caregivers, and how we were a team striving to reach the same goals. Sometimes we struggled to find common ground, but for the most part, we were able to understand and support each other.

As the mother of a son with autism, who is now 27 years old, I remember his therapists at school, and the many, many meetings over the year: some full of joy and pride, others tearful and discouraging, some just tedious and repetitious.

It is noteworthy for me to have both perspectives: I am a mother of a young man severely affected by ASD, and I am also a physical therapist who has worked with children with disabilities, including ASD, for 34 years. I have worked in many settings:acute care, early intervention, NICU, and schools; however, the factor common to all these settings is the constant need to interact with families.

I have been on both sides of the IEP table and have learned much from both viewpoints. My son, Eric, has increased both my awareness of the overwhelming issues parents face as well as my ability to empathize.

At meetings, I see parents and caregivers and I recognize the gamut of emotions: hopefulness, anger, grief, guilt, determination, but, most of all, their profound love for their child. I have attended meetings where there has been a breakdown in communication and understanding, resulting in frustration, anger, and withdrawal.

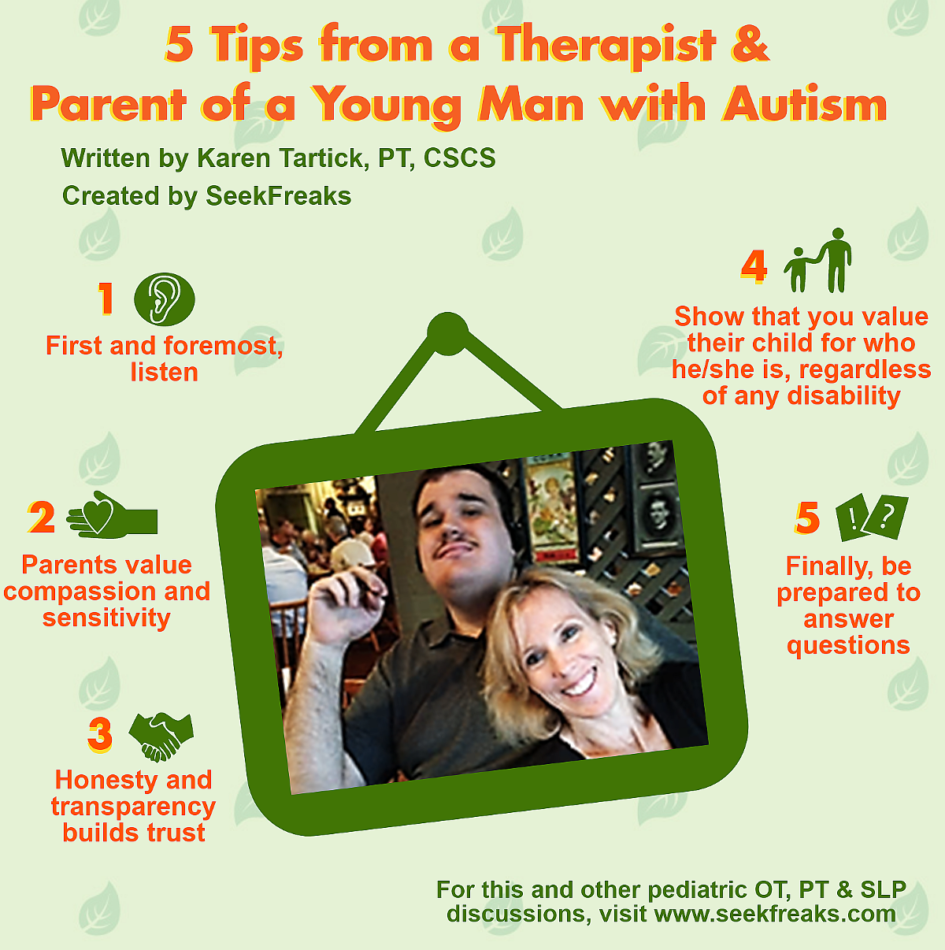

5 Tips from a Therapist and Parent of a Young Man with Autism

Here are some pointers that have helped me to develop good relationships with the families with whom I work, establishing a sense of trust and mutual respect:

1. First and foremost, listen

Close your laptop, look at the parents as they speak, and listen with the intent to understand, not respond. Acknowledge that they are the expert. Hear the perspective and concerns of the parent/caregiver, especially parents of children in the younger ages.

They may still be struggling with denial, grief, anger, or acceptance. Understand that meetings are overwhelming for them. There is often an overload of information, and in trying to advocate for their child, they may be intimidated by all the people speaking about the multiple needs.

Though I have experience with the IEP meeting as both a specialist and a parent, I have often attended an IEP meeting for Eric with a sense of optimism, sit up straight, smile, and do my best to advocate…only to go home frustrated, exhausted and overwhelmed with the “homework” I was given.

I remember one particular IEP meeting when Eric was in high school where the goal set for him was to participate in a game of basketball. I knew that Eric had absolutely no interest in basketball; in fact, he would simply hand us the ball rather than make any attempt to participate.

Evidence shows children with ASD learn when planning and programming are preserved in an emotionally positive situation for the learner (Longuet 2012). Not only could this unrealistic goal been avoided before the meeting by simply seeking out my goals for Eric, it also undermined my trust and belief that the person knew and valued what was important to Eric and our family.

Offer parents the opportunity to observe and participate in a therapy session, thus empowering them and using their knowledge of their child: what motivates them, what are their interests, and what are the common goals for which we should be striving?

Offer to meet with the parents or set up a phone call at a less stressful time than during an IEP meeting where the parent feels more in control, and less intimidated. Use recognized tools (COPM, PEM-CY, CPI) ahead of meetings to be sure the students and/or families goals are recognized.

2. Parents value compassion and sensitivity (Ooi et al. 2016)

Therapists should try to be reasonable when setting expectations. Parents are often juggling multiple roles: being a wife or husband, having a career, meeting the needs of their other children, cooking, cleaning, running errands…the list is seemingly endless.

When expecting a parent to take on the role of “therapist” at home, healthcare professionals need to be understanding and accepting of the time constraints and other responsibilities that the parent has before they consider adding yet another activity per day. Current research suggests that parents of children with autism experience greater stress than parents of children with intellectual disabilities and Down Syndrome (American Autism Society 2011).

Because Eric is nonverbal, he cannot always communicate his needs. Guessing about his wants and needs can often lead to tantrums, aggression, or self-injury. To this day, I have relics of past communication devices at home, that bring a sense of guilt…

If I had worked harder at home with the PECS, PODDS, AAC devices, picture schedules, would Eric be better able to communicate his wants and needs?

And yet, I know that parents like myself do the best we can at the time. As a professional, my role is to set expectations that meet the needs of the parents and their child; as a human being, my support and compassion will reassure and encourage the student.

3. Honesty and transparency builds trust

Looking back on all the interactions I have had with healthcare professionals, I value most the individuals who were honest, and who interacted in a compassionate manner with me. It is important to be honest and sincere about the strengths and needs of a child even when it is difficult for a parent to hear or for a therapist to say.

Acceptance may take years, but it is important to use our knowledge and research to help a parent understand his/her child’s disability. It should not happen as a battle of wills – I recall a meeting where therapists insisted that the student had a diagnosis of autism, and the parents were obviously shocked and distressed by this.

What may seem transparent to us as therapists may not be so to parents. Though honesty is a critical component of any interaction between professionals and parents, it must be expressed with compassion and empathy, and an understanding that the parent may still be grieving the loss of a hope-that one day their child may talk, that one day their child will walk.

Etched into my memory is the first moment I ever heard the word “autism” associated with Eric. I had been a pediatric PT for nine years. How could I have not known??

Yet there it was: I had not considered autism. I am so grateful to the professionals at that meeting who were understanding and compassionate.

I have had to be honest with parents about their expectations of their child being able to walk, or use a power wheelchair, I strive to be compassionate and use strong research which helps the parent, leading to a trusting relationship. Be sure to give them time to process the information; don’t be in a hurry to make them understand.

4. Show that you value their child for who he/she is, regardless of any disability

Communicate in a way that demonstrates you know their child as someone special, not just as a diagnosis.

I’ll always remember the people that have told me a story that showed me that they really knew Eric – not what he needs in speech, OT, or PT, but as a child who at one time loved Thomas the Tank Engine!

Knowing that they looked at Eric as a child first was so valuable to me, and I loved that they seemed to know him as the special person I knew him to be.

Continue to write the occasional positive story/anecdote in a communication folder-those notes would lift my spirits so many days, often at times when I felt I couldn’t take any more notes about his crying, or aggressive behavior.

5. Finally, be prepared to answer questions

This is why knowledge about research and evidence-based practice is critical. Therapists must be informed about current research and EBPs in order to address questions about interventions.

When Eric was first diagnosed, I was given so much random advice about treatments and cures (there is NO cure for autism), and I would research them only to discover there was only anecdotal support.

Frustratingly, the list of treatments was constantly changing: gluten/casein-free, chelation therapy, vitamin B-12, secretin in the gut – these are only a handful of the many experimental treatments people have told me to try.

As a mother, I was desperate for any intervention that would help my son, but as a PT, I realized many suggestions were guesses. There now are established interventions for children and young adults with ASD (Wong et al. 2014).

As a therapist who is encountering more and more children with this diagnosis, I am ethically bound to be knowledgeable about these evidence-based interventions. In a study, parents of children with ASD preferred treatments with empirical support over immediate treatment (Call et al. 2015).

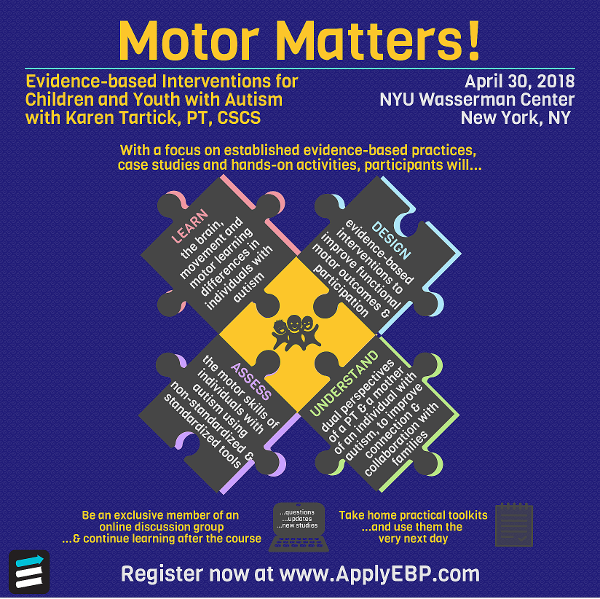

Research has emerged and is now abundant demonstrating motor delays, motor learning differences, dyspraxia, postural, and coordination difficulties(Bhat et al. 2011, Downey & Rapport 2012, Dzuik 2007,Fournier 2010, Green et al. 2009, Miyahara 2013,Whyatt & Craig 2012). As therapists, we can use our knowledge of motor development to facilitate improvement in gross motor skills and enable children with ASD to participate more fully with their peers, leading to increased levels of physical activity and improved overall quality of life. (Bremer & Lloyd 2016, Colebourn et al. 2017, Ketcheson et al 2016, Lang et al. 2010 Mieres et al. 2012 Pan et al. 2015)

My dual perspective, as a mother of a child with a disability and therapist as critical member of a support team, has given me the ability to relate well. Our role as a OTs, PTs and SLPs is to be professional, knowledgeable and up to date on current research and techniques, while also demonstrating compassion, empathy, and support for the family. .

Catch Karen in New York City (April 30) for the dynamic hands-on Motor Matters! Evidence-based Interventions for Children and Youth with Autism where she shares her expertise and experiences as a pediatric therapist and mother of a son with autism.

Resources

Bhat, A. Landa, R. J., & Galloway, J. C. (2011). Current Perspectives on Motor Functioning in Infants, Children, and Adults With Autism Spectrum Disorders. Physical Therapy. 91(7), 1116-1129.

Bremer E., Lloyd M (2016) School-based fundamental-motor-skill intervention for children with autism-like characteristics: an exploratory study. Adapted Physical Activity Quarterly, 33(1), 66-88.

Call, N., Delfs, C., Reavis, A., Mevers, J.L. (2015). Factors influencing treatment decisions by parents for their children with autism spectrum disorder. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 15-16, 10-20.

Colebourn, J.A., Golub-Victor, A.C. Paez, A. (2017). Developing Overhand Throwing Skills for a Child with Autism With a Collaborative Approach in School-Based Therapy Pediatr Phys Ther, (29), 262–269.

Downey R., Rapport M. J. K. (2012). Motor activity in children with autism: a review of current literature. Pediatr. Phys. Ther, (24), 2–20.

Dziuk, M. A., Larson, J. C. G., Apostu, A., Mahone, E. M., Denckla, M. B., Mostofsky, S. H. (2007). Dyspraxia in autism: association with motor, social, and communicative deficits. Developmental Medicine & Child Neurology, 49, 734–739.

Fournier K. A., Hass C. J., Naik S. K., Lodha N., Cauraugh J. H. (2010). Motor coordination in autism spectrum disorders: a synthesis and meta-analysis. J. Autism Dev. Disorders, 40(10), 1227-1240.

Green, D., Charman, T., Pickles, A., Chandler, S., Loucas, T., Simonoff, E., Baird, G. (2009). Impairment in movement skills of children with autism spectrum disorder. Developmental Medicine & Neurology, 51, 311–316.

Ketcheson, L., Hauck, J., Ulrich, D. (2016). The effects of an early motor skill intervention on motor skills, levels of physical activity, and socialization in young children with autism spectrum disorder: A pilot study. Autism, 21(4).

Lang, R., Kern Koegel, L., Ashbaugh K., Regester, A., Ence W., Smith, W. (2010). Physical exercise and individuals with autism spectrum disorders: A systematic review. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 4(4),565-576.

Mieres, A., Kirby, R., Armstrong, K., Murphy, T., Grossman, L. (2012). Autism Spectrum Disorder: An Emerging Opportunity for Physical Therapy. Pediatric Physical Therapy,24(1), 31-37.

Miyahara M. (2013). Meta review of systematic and meta analytic reviews on movement differences, effect of movement based interventions, and the underlying neural mechanisms in autism spectrum disorder. Frontiers in Integrative Neuroscience, 7, 16

Ooi, K. L., Ong, Y. S., Jacob, S. A., & Khan, T. M. (2016). A meta-synthesis on parenting a child with autism. Neuropsychiatric Disease and Treatment, 12, 745–762.

Pan, C., Hsu, P., Chung, I-C., Hung, C., Liu, Y., Lo, S. (2015). Physical activity during the segmented school day in adolescents with and without autism spectrum disorders. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 15-16, 21-28.

Whyatt, C.P. & Craig, C.M. (2012). Motor skills in Children Aged 7-10 Years, Diagnosed with Autism Spectrum Disorder. J Autism Dev Disord, 42(9), 1799-1809.

Wong, C., Odom, S. L., Hume, K. Cox, A. W., Fettig, A., Kucharczyk, S., … Schultz, T. R. (2014). Evidence-based practices for children, youth, and young adults with Autism Spectrum Disorder. Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina, Frank Porter Graham Child Development Institute, Autism Evidence-Based Practice Review Group.

January 3, 2024 at 10:37 pm

2t5bu3