Written by Cindy Dodds, PT, PhD. She is an Associate Professor at the Medical University of South Carolina’s College of Health Professions. Her clinical and research interest focus on children with medical complexity. Her passion in this area has led her to become a co-founder of a public charter school serving children with multiple disabilities.

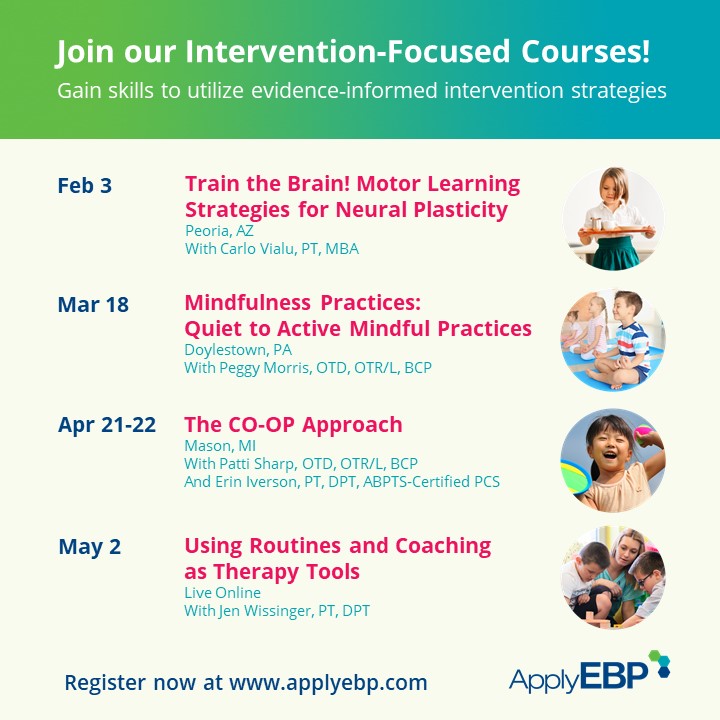

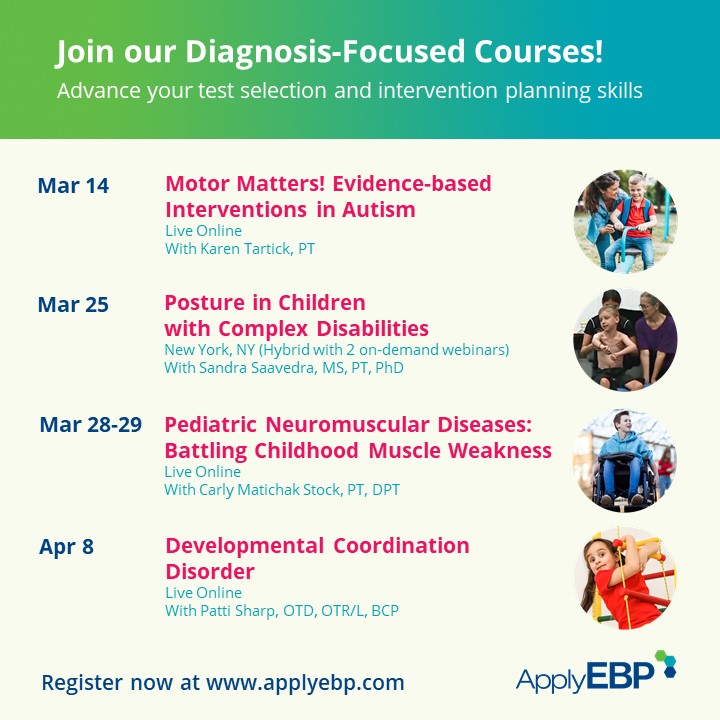

Join us at these evidence-based courses:

In 1997, Barbara deLateur recognized, “Those in rehabilitation medicine have a history to be proud of: following our intuition based on professional experience and altruistic instincts, we have always valued quality of life, encouraging our patients to strive for the highest goals to which they aspired, and providing the technical assistance needed to make those aspirations a reality.”

Most therapists likely agree with Barbara’s statement, but the ability to actually practice this way is challenging because of productivity standards, funding restrictions, educational and socioeconomical characteristics of families, healthcare and educational infrastructure, fear of legal penalties, and others.

For children with complex disabilities (CCD) and the therapists who serve them, these difficulties are further compounded by the addition of children’s multiple and complex impairments. So, what to do? The suggestion put forth here is to consider a quality of life model when serving and caring for children with complex disabilities.

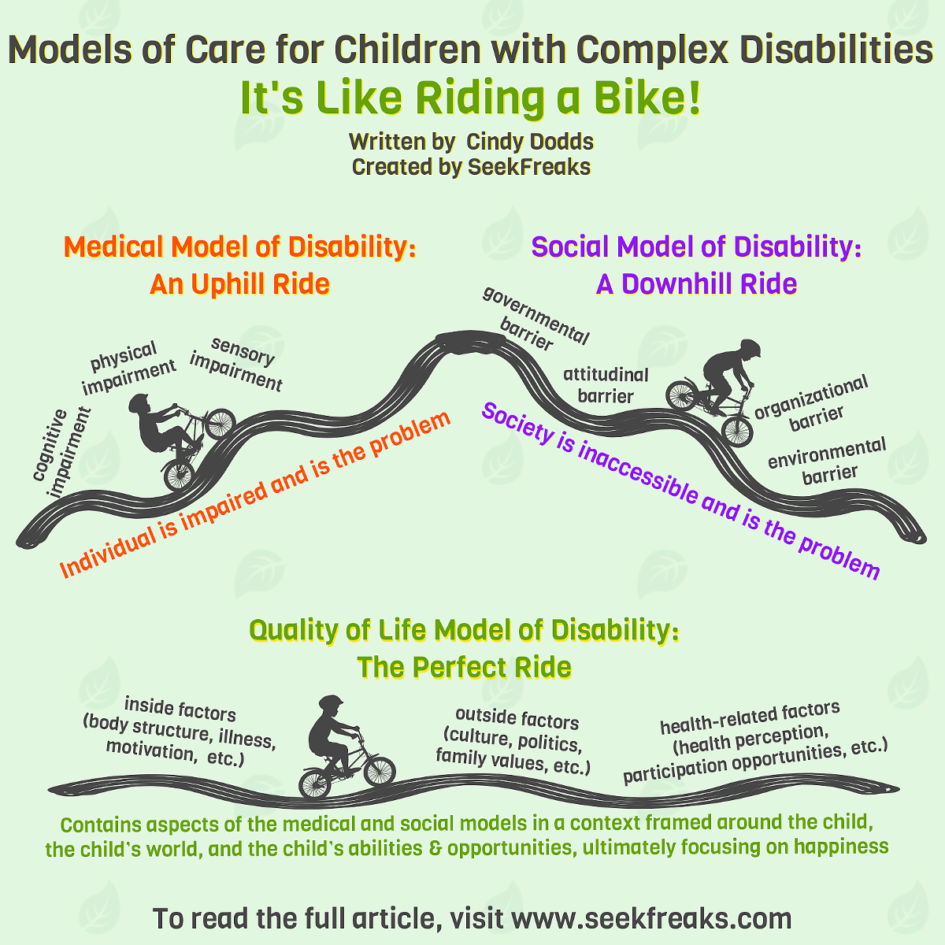

Medical Model: An Uphill Ride

Children with complex disabilities are dependent on others for mobility, self-care and communication. Often a primary disability co-occurs with conditions such as seizure disorder, sensory impairments including vision and hearing, and cognitive deficits. Because of these multiple impairments, families and therapists frequently become overwhelmed, swamped, and engulfed by a medical model (Figure 1).

A medical model works to “fix” impairments in CCD with little to no regard if “fixing” is realistic or how it feels to be on the receiving end = “getting fixed”. In this model, CCD are viewed as problems to be “fixed” rather than people having the right to be different, accepted, and valued by family, friends, and community. Medical interventions to improve impairments in CCD can be a wise choice, but decisions to “fix” should be framed around the true context of the child’s impairments, abilities, as well as family and community life.

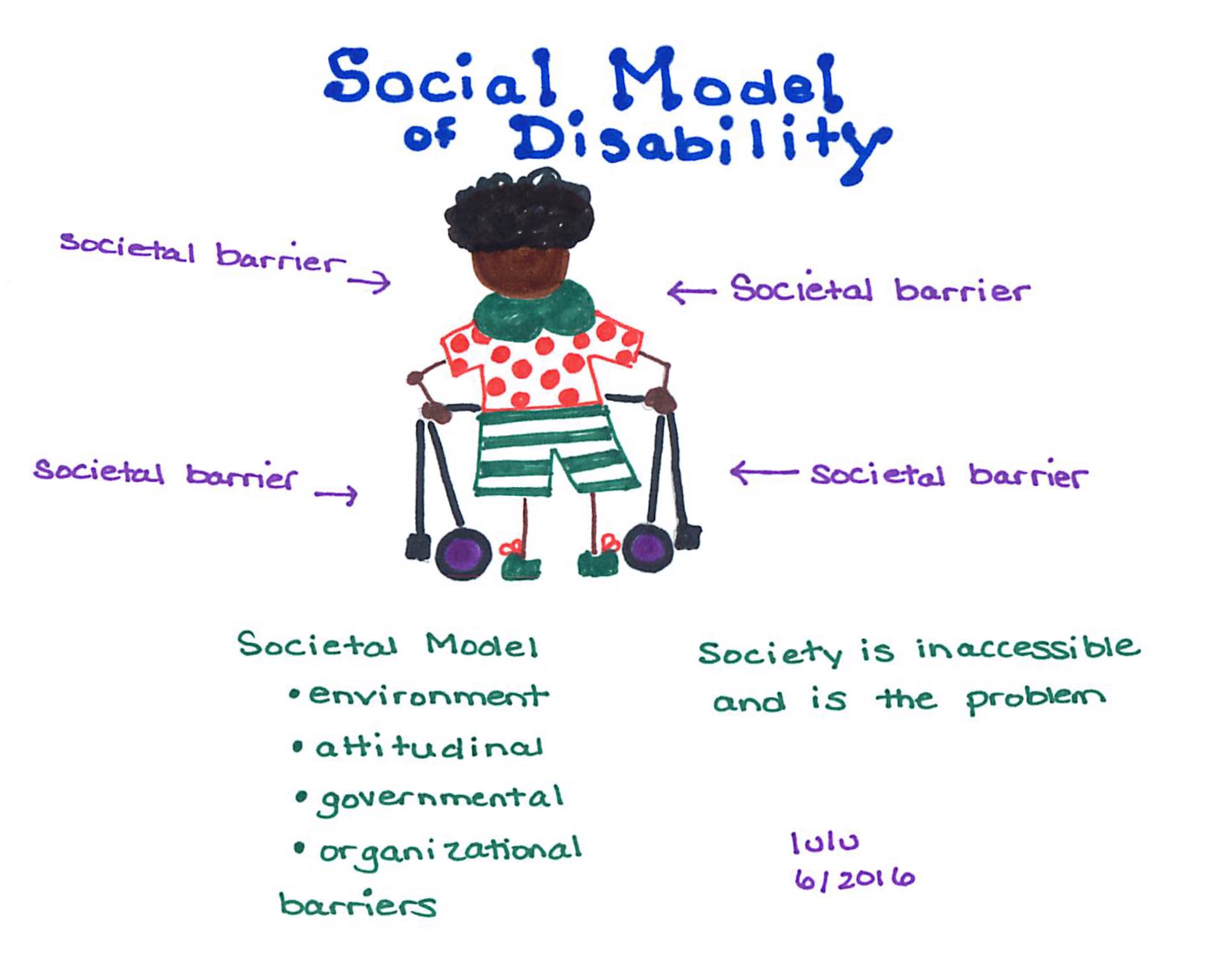

Social Model: A Downhill Ride

In a social model of disability (Figure 2), rather than the individual being the problem to solve or fix; society is viewed as the problem. The problem is because of environmental, attitudinal, governmental, and organizational barriers. While CCD should not be considered the problem, it does seem unreasonable to expect society to address, flex and adapt to each and every specific impairment of CCD.

Quality of Life Model: The Perfect Ride

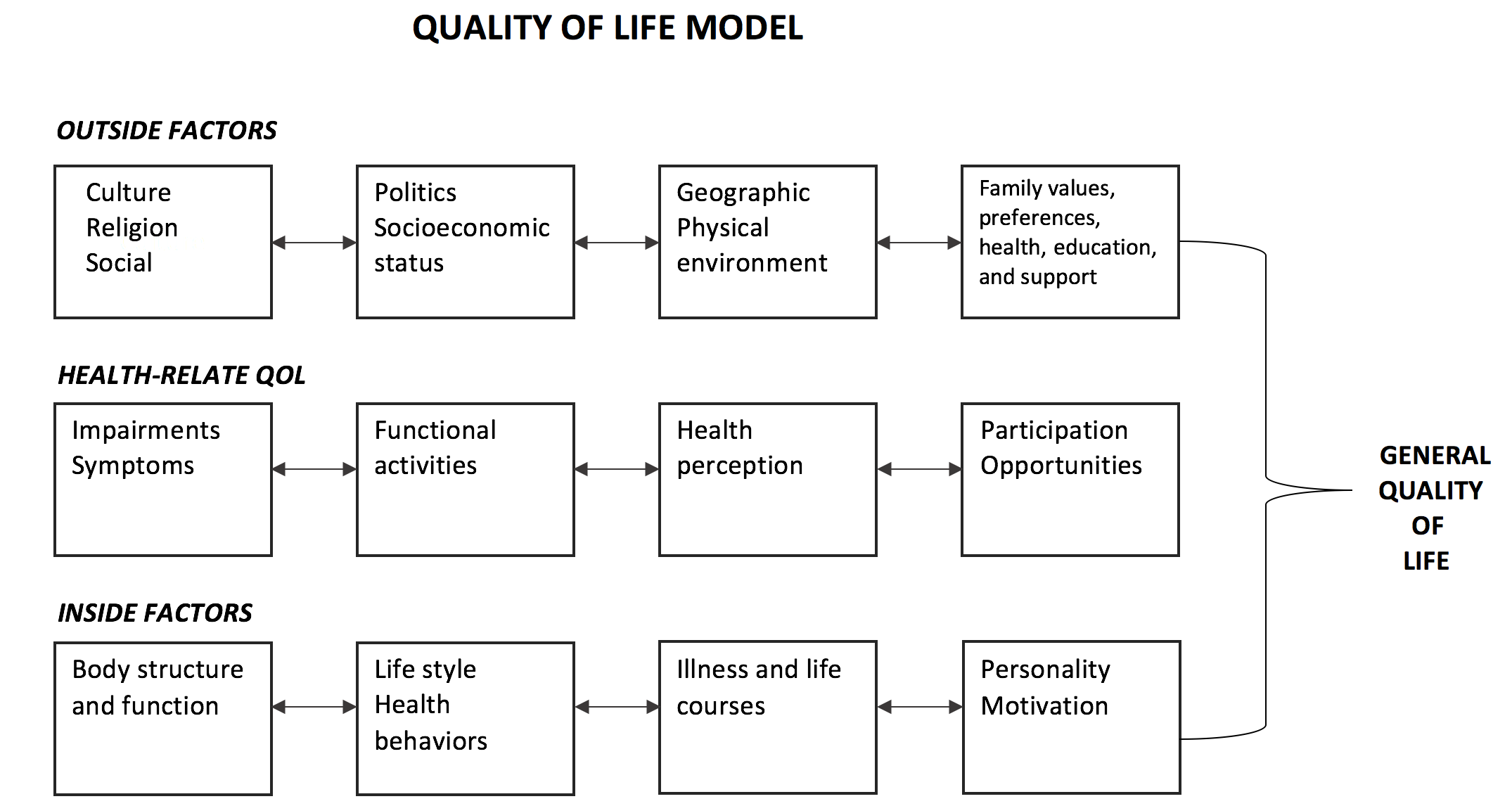

A quality of life (QoL) model, such as the one created by Patrick and Chiang, contains aspects of the both medical and social models in a context framed around the child, the child’s world, and the child’s abilities and opportunities, ultimately focusing on happiness.

Source: Patrick and Chiang, 2000

For CCD considered within a quality of life QoL model,

- Internal factors address aspect beneath the skin such as spasticity, awareness, disease progression.

- Therapy message: focus to improve body impairments that will enhance health, well-being and happiness.

- Culture, religion, physical environment, socio economics, factors external or outside of the skin, are respected.

- Therapy message: Meet a child and family in the context of their world and respect that their world may (could and should) look different from yours.

- Health related QoL factors which highlight abilities, opportunities, and participation, are highly valued.

- Therapy message: Therapists are able to identify children’s abilities, encourage creative opportunities and participation in home, school and communities.

When considered collectively, these factors interact to generate and support well-being and happiness of CCD and their families.

Laurie Ray: Thank you Dr. Dodds (Cindy!) for this inspiring post! Many of us have likely moved between these models throughout our careers.

SeekFreaks, focusing on a child’s quality of life may be a moving target but also a persistent goal that can bring the best out of the children and families we serve and ourselves.

What do you think? Does school-based practice lean towards one of these models currently? Are there benefits, for schools and students, from each of these models? Which best aligns with how you practice? If you were to adopt a Quality of Life model, what would change in your practice? I am intrigued!

The QoL model fits so well with challenges to work from a strength-based approach. I can see how a focus on improving each child’s life is such meaningful work that we are equipped to address. I want to hear how you SeekFreaks out there are applying the QoL model to your work!

Join us at these all evidence-based, all practical continuing education courses:

References

- deLateur, B.J. Quality of Life: A Patient-Centered Outcome. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation. 1997; 78:237-39.

- Reiter S, David D. The educational and treatment concept of Israeli service provider-special education teachers, professionals, direct care staff and consumer-parents.British journal of developmental disabilities. 1996;XLII(82):32-44.

- Patrick DL, Chiang YP. Measurement of health outcomes in treatment effectiveness evaluations: conceptual and methodological challenges. Medical care. 2000;38(9 Suppl):II14-25.

April 25, 2018 at 3:56 pm

I think the QoL model aligns well with the ICF. As a school-based practitioner, I find that if I can help my teams (parents, teachers, and student) focus first on the desired activity it helps them to expand their thinking to the multiple ways of increasing a student’s function. I think the QoL model provides some additional language and structure for framing the conversation in ways which will help IEP teams find ways to increase the student’s ability to engage in learning, work, and leisure activities…. absolutely increasing their quality of life!

May 14, 2019 at 10:37 am

Such a cool insight, Carlynn! It is so important to focus all our efforts for students with complex needs on what is MEANINGFUL!!