Written by Erin Iverson, PT, DPT, PCS. Erin is a Certified CO-OP Instructor. She is an outpatient, pediatric physical therapist at Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center (CCHMC). Erin is contributing to the development of the Clinical Practice Guideline for Developmental Coordination Disorder (DCD) sponsored by the APTA. She is also co-leader of the DCD Translating Research and Clinical Knowledge Team at CCHMC. She has a strong passion for teaching other therapists via her course The CO-OP Approach. More info on relevant courses after the article below.

Developmental Coordination Disorder (DCD)

Developmental Coordination Disorder (DCD) seems to be a buzzword these days and for good reason! Literature reports that DCD affects 5-6% of the population (APA,2013) though two years ago, while working at a large pediatric hospital, I was not treating a single patient with a formal DCD diagnosis.

I was certainly treating children who fit the description of DCD, but children were not entering our clinic doors with the diagnosis in hand. They typically came in with a referral for

- “lack of coordination”

- “gross motor delay”

- or even “pes planus”

Sound familiar?! Their families had no idea that their “lack of coordination” was really part of a much larger diagnosis.

Children with DCD present in a number of ways.

- They typically demonstrate poor acquisition and performance of gross and/or fine motor skills.

- You may also notice lower muscle tone, mild hypermobility, functional strength deficits, postural issues, and balance problems.

These deficits can lead to

- academic and behavioral issues

- lower perceived competence in physical, cognitive and social activities,

- higher levels of anxiety, depression and loneliness

- greater experience of social rejection, teasing and bullying

- lower self-esteem, quality of life, and life satisfaction (Zwicker, 2018)

They may also have co-occurring conditions of ADHD, sensory processing difficulties, behavioral concerns, anxiety, and/or ASD (Blank, 2019).

Perhaps what affects me most with these children is how their coordination deficits impact their relationships with their families. I’ve had families describe their children as lazy, insubordinate, and they were hard to include in family activities. Such a wide range of issues though they can all be attributed to a single diagnosis!

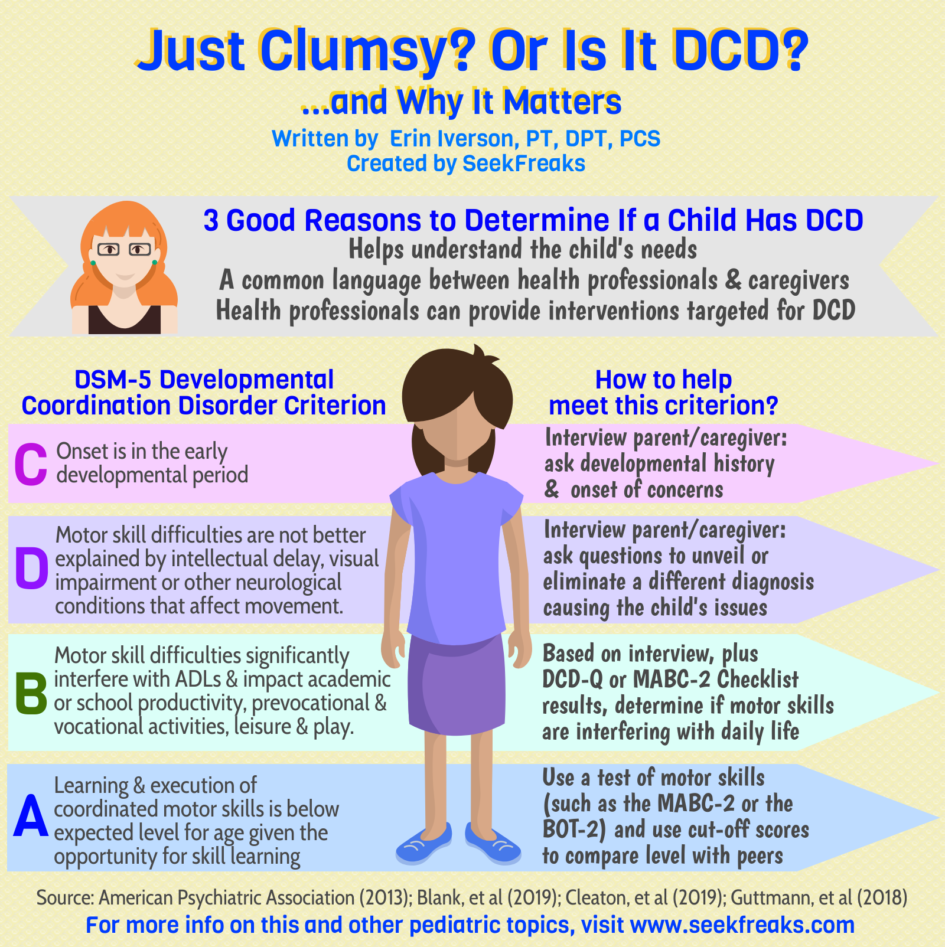

Does It Even Matter If the Child Receives a Formal Diagnosis of DCD?

The answer is yes! Why? Here are a few reasons:

- Understanding of the Child’s Needs: A diagnosis can provide caregivers a more comprehensive understanding of the disorder and provide an explanation for their child’s impairments. DCD is not typically diagnosed until the age of five, though many children go much longer without a diagnosis – some their entire life!

- A Common Language: A diagnosis can also help the child receive proper services and provide a common language between caregivers and medical professionals.

- Apply Interventions Targeted for DCD: Early intervention and treatment for children with DCD can help the child with more than just motor skills. Early treatment can promote motor skill acquisition, encourage strategy use to aid in motor planning (especially if CO-OP is used, but more on this later), and potentially prevent secondary medical complications by encouraging the child to participate in sports and physical activities rather than engaging in a sedentary lifestyle.

Cleaton reports, “having a child with DCD has a considerable impact on families. This needs to be recognized by healthcare and other professionals; otherwise, services and support may not be appropriately targeted and the negative sequelae of DCD may ripple beyond the individual with costly social and economic consequences.” (Cleaton, 2019).

It is our obligation to help these kids receive a diagnosis if they do not already have one.

DSM-5 Criteria for DCD

Okay, okay! We know that early diagnosis is beneficial…but where do we start? The DSM-5 states there are four criteria that must be met to receive a DCD diagnosis by a physician.

A) Learning and execution of coordinated motor skills is below expected level for age, given opportunity for skill learning.

B) Motor skill difficulties significantly interfere with activities of daily living and impact academic/school productivity, prevocational and vocational activities, leisure and play.

C) Onset is in the early developmental period.

D) Motor skill difficulties are not better explained by intellectual delay, visual impairment or other neurological conditions that affect movement.

Let me be clear: a medical diagnosis is the charge of a physician! As therapists, what we can do is to gather and provide information that can help the physician get a full picture of the child’s motor abilities and deficits.

We will go through each criterion and discuss the therapist’s role in acquiring the information for the physician. Typically, I examine the four criteria in a different order than listed in the DSM-5 as it flows better with my evaluation. I will list and discuss the criteria in the modified order below.

Criterion C: Onset is in the early developmental period

Families typically report coordination deficits from an early age, though they may not seek therapy services until the child reaches school age. This may be secondary to the increased demands placed on the child in an organized school setting (handwriting, gym class, engaging with kids at recess). Parents may also begin to compare their children with their peers and realize that they are not able to engage in similar activities.

While some children do start therapy before school age for their “lack of coordination”, the formal diagnosis of DCD is not typically given until the child is five years of age. Why? Some young children are just late bloomers motor-wise! By the age of five, children should have outgrown general coordination issues, have received more opportunities to experience motor activities, and may simply catch up on skills.

How to help meet this criterion: Therapists can document that the onset was in the early developmental period after performing a parent/caregiver interview. Be sure to ask about developmental history and onset of concerns to ensure that the lack of coordination is an ongoing problem without a sudden onset.

Criterion D: Motor skill difficulties are not better explained by intellectual delay, visual impairment or other neurological conditions that affect movement.

Children with DCD may have mild intellectual delay or difficulties in school, but their IQ must not be the cause of their physical abilities. IQ testing is not required for a DCD diagnosis, but it may be beneficial if the child is demonstrating deficits in school.

The child may also not demonstrate visual impairment or other neurological conditions such as cerebral palsy, muscular dystrophy, or a genetic condition that explains the coordination deficits.

How to help meet this criterion: Therapists should continue their parent/caregiver interview to gain a full picture of the child’s birth history, developmental history, family history, onset of concerns, academic history and medication use. Questions should attempt to unveil a different diagnosis causing the child’s issues.

Criterion B: Motor skill difficulties significantly interfere with activities of daily living and impact academic/school productivity, prevocational and vocational activities, leisure and play.

While performing your subjective interview, you should ask open-ended questions about the child’s involvement in activities and participation in various aspects of their life. Ask about motor skills the child should be performing for their age. For example, can the child:

- Ride a bike?

- Get themselves dressed in the morning?

- Make a snack?

- Play outside with neighborhood friends?

- Participate in sports?

- Write?

Try to get an idea of how their deficits impact their daily life. You can click here for a DCD interview guide from CanChild to help guide your questioning.

In addition to your interview, there are multiple questionnaires you can use to meet Criterion B. We will discuss two common screens, the Developmental Coordination Disorder Questionnaire (DCDQ) and the Movement Assessment Battery for Children, Second Edition Checklist (MABC-2-C).

Developmental Coordination Disorder Questionnaire (DCDQ)

- A questionnaire for children aged 5-15 to determine if their coordination deficits affect multiple areas of their lives (home, school, play)

- It’s free, just click here

- Has 15 questions, answered using a 5-point Likert scale

- Completed by parents or caregivers

- Takes approximately 10 minutes

- Has a sensitivity of 85% and an overall specificity of 71%

One nice feature of the DCD is that the actual questionnaire does not have the words “Developmental Coordination Disorder” on it. That way if you are not quite ready to talk about the diagnosis of DCD but want to assess their coordination, you can provide the questionnaire without the pressure of discussing the diagnosis at that time.

Movement Assessment Battery for Children – 2nd Edition: Checklist (MABC-2-C)

- Checklist for children aged 5-12 to assess movement in everyday situations including home and the classroom

- Also measures the child’s attitudes and feelings towards motor skills and how their attitudes may affect their skills

- Includes 30 questions

- Completed by a parent, caregiver, or teacher

- Takes approximately 10-20 minutes.

- Not free! The MABC-2 Checklist is included in the purchase of the MABC-2. The MABC-2 Checklist has a low sensitivity at 41% and an acceptable specificity at 88%.

An interesting feature of the MABC-2 Checklist is that the scores are explained using a traffic light using green, amber, and red as the levels of concern for DCD. This feature provides an easy visual to use when discussing the results with the caregiver.

How to help meet this criterion: Use the results of your interview, plus that of the DCD-Q or MABC-2 Checklist to determine if the child’s motor skills are interfering with his/her daily life.

Criterion A

Learning and execution of coordinated motor skills is below expected level for age, given opportunity for skill learning

If your subjective history taking reveals deficits that began in the early developmental period, the child does not have any exclusionary diagnoses, and they had a positive screen on a questionnaire, then you should perform a standardized test to satisfy Criterion A.

You also need to ensure that the child has been given an opportunity to learn or perform the age-appropriate skills. For example, if a caregiver reports that the child cannot ride a bike but has never been around a bike, then we need to provide the opportunity to try and learn it before jumping to a diagnosis of DCD.

Performing a standardized motor test with the child will show you if their motor skills are lower than that expected for their age. There are multiple tests you can use to assess their motor skill performance. The test should include multiple sections that address different categories of motor skills (such as fine motor, gross motor, balance, strength, etc.) rather than assessing only one activity like handwriting.

Two standardized tests often used in the DCD literature are the Movement Assessment Battery for Children – 2nd Edition (MABC-2) and the Bruininks-Oseretsky Test of Motor Proficiency – 2nd Edition (BOT-2).

Movement Assessment Battery for Children – 2nd Edition (MABC-2)

- Most commonly used standardized test to assess motor skills of children with possible DCD in the literature (Blank, 2019)

- Norm-referenced test for children aged 3-16 years

- 3 sections covering fine and gross motor skills:

- Manual dexterity

- Throwing and catching

- Balance

- Takes 30-45 minutes

The MABC-2 does not specifically diagnose DCD. However, it does reveal if the child has a motor skill deficit. As with the MABC-2 Checklist, this test also uses the traffic light system to describe the severity of motor impairment. A cut off score of ≤ 5th percentile (~2 standard deviation) indicates significant motor skill deficits, while a cut off score of the 16th percentile (~1 standard deviation) identifies that a degree of motor skill deficit is present. (Blank, 2019).

A nice quality of the MABC-2 is that it assesses motor skills both quantitatively and qualitatively so you can document how the skills were performed. One aspect I like about the MABC-2 is that it also prompts you to look at non-motor factors that may be contributing to their motor performance (e.g., is the child hesitant, anxious, disorganized, etc.).

Bruininks-Oseretsky Test of Motor Proficiency – 2nd Edition (BOT-2)

- Norm-referenced test for children between the ages of 4-21 yers

- There are multiple ways the test can be conducted with different lengths of time to complete:

- Short Form – 15-20 minutes

- Complete Form – 45-60 minutes

- 2 Sections:

- Fine Motor: 25-30 minutes (4 fine motor sections: Fine Motor Precision, Fine Motor Integration, Manual Dexterity, Bilateral Coordination)

- Gross Motor: 25-30 minutes (4 gross motor sections: Balance, Running Speed & Agility, Upper-Limb Coordination, Strength)

Again, you can use scores 1 SD below norm as a cut off value. (Blank, 2019)

How to help meet this criterion: Use the cut-off scores to indicate whether the child’s execution of coordinated motor skills is below expected level for age, given opportunities for learning.

What to Do with This Information

Now this part completely depends on the regulations of your employer/facility/setting. So, first, I will describe to you what I do in the hospital where I work. You may choose to follow this if it fits in with your regulations and/or after discussing it with your supervisor. If it does not fit with your regulations/procedures, continue reading below under the heading How this Information Influences My Interventions.

What I Do

So now I have the necessary information on whether my client meets the DSM-5 criteria for a DCD diagnosis. This is where the physician comes in. I typically send a letter to the referring physician with the DSM-5 criteria listed and the child’s scores of the DCDQ, standardized test I used, and their history leading me to believe they may qualify for a DCD diagnosis.

At the bottom of the letter, I add the following statement:

___ This child meets criteria for DCD

___ This child DOES NOT meet criteria for DCD because ________________________

Physician signature: ____________________

Date: _____________________

Then the doctor can sign it and fax it back easily so I know if they think the diagnosis is applicable. Note that the communication may be different for your facility/setting.

I have had some doctors think that I am requesting imaging to rule out diagnoses, such as Cerebral Palsy. Formal imaging or testing is not required to rule out any exclusionary diagnoses unless there is a specific concern for them (e.g., a child demonstrates asymmetries in their extremity use so perhaps other tests would be beneficial to rule out cerebral palsy).

DCD is so under-diagnosed in my area that I want to spread the news and hopefully reach more children with DCD! So, in addition to the child’s scores, I also attach a DCD Fact Sheet so the physician can read more about DCD. We created one at the hospital in which I work; you can also develop one yourself or use the Physician Fact Sheet from CanChild!

How this Information Affects My Interventions

Often there is a lag time to hear back from the physician providing a DCD diagnosis. Or, in some cases, I am unable to get a formal diagnosis of DCD (which may be what you are dealing with). This is ok…at least I still have the knowledge provided by the results of the testing I mentioned above for each criterion. Plus, I have my clinical expertise to utilize these results in my clinical reasoning to apply the best available evidence about working with children with motor coordination difficulties. (FYI, I avoid using the term DCD when not diagnosed by a physician. Rather, I refer to the child as having motor coordination difficulties, or the like.)

What I do? I start treating using the recommended interventions for children with coordination difficulties. Research shows that using a top-down approach focusing on activity limitations and participation restrictions is the best treatment for children with DCD (Blank, 2019).

Simply working on activities to address balance, strength, or bimanual coordination has not been shown to impact patient goals as well as focusing on their actual goal.

For example, if a child wants to play soccer with their neighbors, your treatment should address the elements of playing soccer such as kicking, passing, dribbling, throwing in the ball, or understanding the rules of the game.

Simply working on structural or functional impairments like doing squats to improve leg strength, standing on one leg to improve balance while kicking, or doing jumping jacks to improve bimanual coordination for soccer drills will not likely improve their soccer skills.

For the recommended top-down interventions for children with DCD, you can read Blank et al, 2019. Here are the primary interventions:

- Cognitive Orientation of daily Occupational Performance (CO-OP)

- Neuromotor Task Training

- Motor imagery

- Task-specific training

As an additional resource (especially for those who work in school-based practice), visit and download CanChild’s M.A.T.C.H. Flyers for Educators. Notice that one set is labeled “DCD”, while another set is labeled “Coordination Difficulties.”

For more information on top-down approaches, you can also read Patti Sharp, OTD, OTR/L’s SeekFreaks article How a Cartwheel Flipped my Practice Right Side Up!

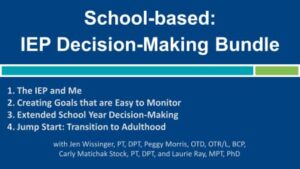

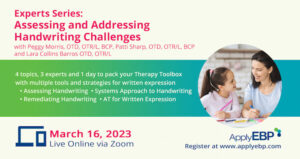

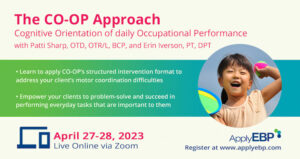

Catch some courses on DCD from Apply EBP.

Click on an image below for more details.

References:

American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed.). Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Publishing.

Blank, R., Barrett, A., Cairney, J., Green, D., Kirby, A., et. al. (2019). International clinical practice recommendations on the definition, diagnosis, assessment, intervention, and psychosocial aspects of developmental coordination disorder. Developmental Medicine and Child Neurology. 61: 242-285. DOI: 10.1111/dmcn.14132

Cleaton, M.A.M., Lorgelly, P.K. & Kirby, A. (2019) Developmental coordination disorder: the impact on the family. Quality of life Research. 28(4): 925-934. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-018-2075-1

Guttmann, K., Flibotte, J., DeMauro, S. (2018). Parental Perspectives on Diagnosis and prognosis of neonatal intensive care unit graduates with cerebral palsy. The Journal of Pediatrics. 203:156-162. Doi: 1016/j.jpeds.2018.07.089

January 3, 2024 at 10:41 pm

e9ysuk