The author, Carlo Vialu, PT, MBA, is co-creator of SeekFreaks. He loves promoting function and participation for children and youth with disabilities, from our assessment to our interventions, via his continuing education courses at Apply EBP. More about these courses after the article below.

Oh was I excited when I ran into the article Visual Function Classification System for Children with Cerebral Palsy by Baranello, et al (2019). I have been wanting to update SeekFreaks’ Functional Classification Systems article, and now have the best reason to do it. In addition to this new system, I will also be updating in this article the studies on stability of the different systems that have been published since the last time I wrote about it.

Let’s embrace lifelong learning and update our knowledge of these classification systems.

Cerebral palsy (CP) is the most common childhood motor disability. The Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) reports prevalence between 1.5-4 per 1,000 children worldwide, and between 3.1-3.6 per 1,000 children in the United States.

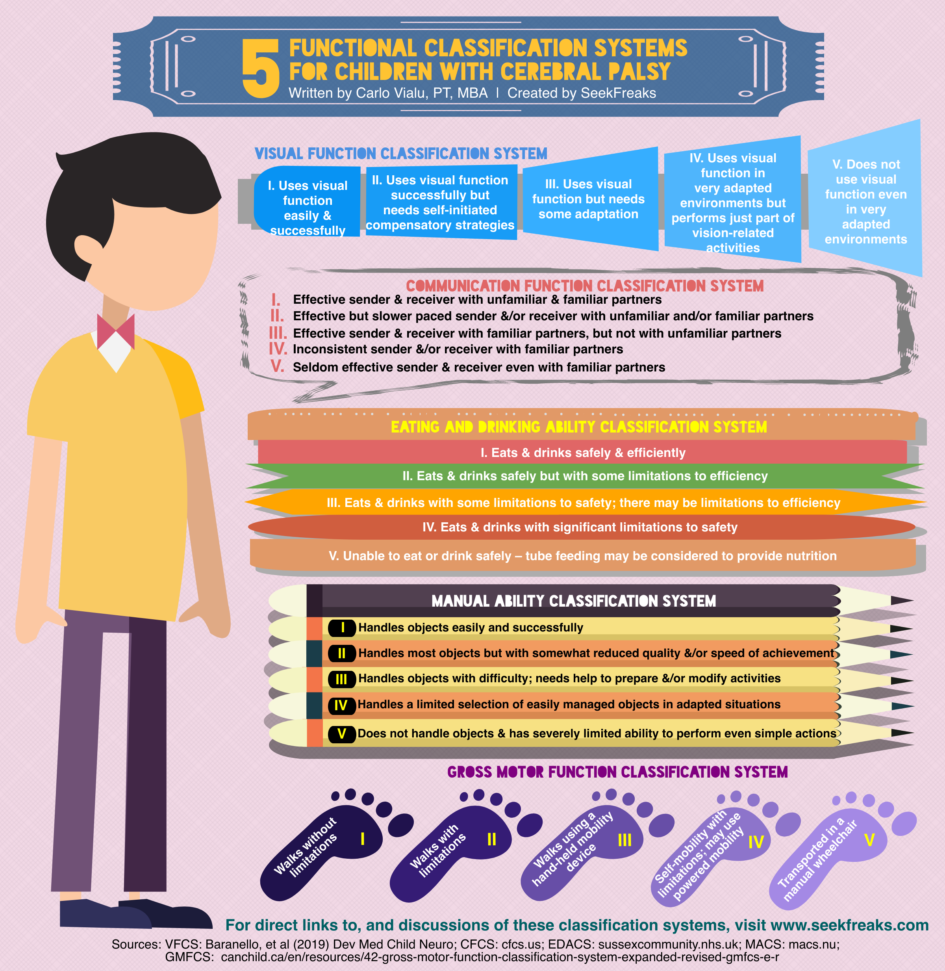

April 1997 became a pivotal month when the article on the development of the Gross Motor Functional Classification System (GMFCS) was published. With the eventual adoption of the GMFCS by researchers and rehabilitation professionals working with individuals with CP, other classification systems were developed. These include the Manual Ability Classification System (MACS), Communication Function Classification System (CFCS), the Eating and Drinking Ability Classification System (EDACS), and most recently, the Visual Function Classification System (VFCS).

This week I put them all together in one infographic as a quick reference for rehabilitation professionals, educators and families. I will also discuss how functional classifications are helpful in school-based practice, and provide you with the information and resources for each.

Utilizing the Functional Classification Systems

There are a few things to keep in mind when using these classification systems:

- The 5 levels in each classification system are broad categories that represent “clinically meaningful distinctions” in function. They are not detailed assessments of function. When limitation is noted with any of these classification systems, it is recommended that you utilize additional assessment tools to determine specific information on performance or impairments that impact the child’s ability to participate in school.

- These classifications rate performance, not capacity. While capacity is the best that the child can do, performance refers to what the child usually does in his or her current environment.

- The scales used by the classification systems are not ordinal. Although they distinguish different levels of function, the distances between levels (in terms of performance) are not equal. Neither are individuals with CP distributed evenly across the 5 levels of each classification system.

- Each classification system should be rated independently. In many cases, the child will have different levels under each classification system. For example, a child with a GMFCS Level II may have a MACS Level III, a CFCS Level IV, an EDACS Level I, and a VFCS Level II. Hidecker et al (2012) found that among 222 children with CP, only 36 or 16% had the same GMFCS, MACS and CFCS levels (EDACS and VFCS was not included in this study). Baranello et al, (2019) found only moderate correlation between the VFCS and each of the other classification systems. Compagnone et al (2014) found that strong correlation among the GMFCS, MACS and CFCS was limited to those classified as Level V – i.e., a child with severe disabilities due to CP is likely to have the lowest levels of mobility, manual and communication skills.

- If you are undecided when classifying between 2 levels, refer specific guidance on differentiating between 2 levels. At times, there may be no clear choice. In fact, if you look at the motor growth curves for each GMFCS level, you can see a wide range of abilities within each level that appear to overlap with those of the next lower or higher level. For example, you may think that a child is either functioning in the higher percentiles of GMFCS Level IV or in the lower percentiles of GMFCS Level III. In cases like this, choose the level that best fit the child’s everyday function and record the reason for your decision for clarification and future reference.

Update: Stability of the Classification Systems

A stable classification system means that it is a good tool for predicting function, and thus intervention planning. As such, studies have been conducted to test the stability of these classification systems.

The GMFCS continues to be found to be stable. Thus, it is a good prognostication tool. (Palisano et al, 2006 – 73% of children remained at the same level; Palisano et al, 2019) A child who was classified as GMFCS Level IV before his/her 2nd birthday, for example, will likely still be at Level IV at age 12. This information, though sobering, can be used now to plan and address the child’s current and possible future needs. An early introduction of power mobility for this child can address current mobility needs, while also ensuring that he/she achieves proficiency using the device that will likely still be needed at age 12.

A study of the MACS by Ohrvall, et al in 2013, showed the MACS to be stable, as well…70% of children between the ages of 4-17 years old stayed at the same level. Thus, a classification of MACS Level II can lead to exploration of compensatory strategies that can facilitate handling abilities now and in the future. Palisano, et al (2019), however, found only 49.1% of children 4 years and older did not change levels. A further study by Burgess, et al (2019), was able to tease out the highest stability for MACS Levels I (76%) and V (83%); followed by MACS Level 2 (67%); and the lowest for MACS Levels III (50%) and IV (51%). The authors explained that “the relative stability of the MACS levels can be explained by the proportion of each children in each level” – in many of the studies, fewer children were classified as Levels III and IV, compared to other levels.

A recent study on the EDACS by Sellers, et al (2019) found the EDACS to be stable over 6 or more years in 86% of the cases. Palisano, et al (2019) found the CFCS to remain the same only in 55% of children older than 4 years old.

Some other lessons from these studies on stability:

- Children younger than 4 years old demonstrated less stable GMFCS (58.2%), MACS (30.3%) and CFCS (39.3%). Therefore, repeated classification is recommended by Palisano, et al (2019), especially at a younger age. The authors hypothesized that the GMFCS’ age band descriptions (i.e., different GMFCS levels descriptions for <2 years old, between 2-4 years old, between 4-6 years old, between 6-12 years old, and between 12-18 years old) may be one of the reasons for the higher agreement for the GMFCS. For this same reason…

- Use the Mini-MACS for children ages 1-4 years old. None of the studies mentioned above utilized the Mini-MACS as the younger sibling of the MACS was created after data-gathering were completed for the above studies.

- Most changes in levels were +1 or -1 movements. This means, that while changes may occur, no wild swings from, say Level IV or V to Level I should be expected. So take this into consideration when prognosticating and planning interventions.

- What may account for these changes?

- Burgess, et al (2019) stated that the “influences of cognition, motivation, or culture on what a child does on a daily basis will impact on MACS ratings”, so while the child may have the potential to be at a higher level, such performance may not be observable because of any of the influences listed above.

- Sellers, et al (2019) noted changes in EDACS in adolescence, such as a child that increased 1 level due to acquiring new skills, and 2 children that developed orthopedic and postural changes that lowered their levels.

- I would also add that by my own experience there is some degree of subjectivity involved, especially when the child appears to be exactly in the middle of 2 level descriptions, and when they are younger and their level of abilities is not that clear yet. Hence, the need to document why you assigned a certain level to the child.

Use all 5 classification systems for better communication and collaboration

- It is highly recommended to use all 5 classification systems to provide a comprehensive picture of the child’s overall function.

- If the whole team adopts their use, the team will also gain a common language, and a similar awareness or knowledge of the child’s abilities. This can then become a basis for collaboration, from assessment, to goal setting, and implementing coordinated interventions for the child.

Planning interventions

- Since the classification systems capture the child’s general function, they are great tools for planning interventions.

- You know to allow the child to explore self-initiated strategies to complete the task within their abilities. Or you can engage the family and educators in trying out and implementing compensatory strategies that provide the child the ability to be independent right away (e.g., mobility devices, adaptive utensils for eating, communication devices).

- You can also design interventions that can help the child improve their function or to prevent secondary impairments (e.g., positioning devices and exercises to prevent secondary impairments that may affect function such as that described above about postural changes decreasing EDACS Level).

Here are some basic information and resources for the 5 classification systems:

Gross Motor Functional Classification System (GMFCS)

The Basics

- The GMFCS was developed to classify mobility of individuals with CP.

- It includes 5 Levels:

- LEVEL I – Walks without Limitations

- LEVEL II – Walks with Limitations

- LEVEL III – Walks Using a Hand-Held Mobility Device

- LEVEL IV – Self-Mobility with Limitations; May Use Powered Mobility

- LEVEL V – Transported in a Manual Wheelchair

- The instructions are available here: Gross Motor Classification System – Expanded & Revised (GMFCS – E&R). I recommend that you read it, and keep it handy.

- To further facilitate correct classification, it describes distinctions between levels that are next to each other (e.g., Level I vs. Level II, Level II vs. Level III, etc.)

- It includes descriptors for each level under 5 age groups:

- Before 2nd Birthday

- Between 2nd & 4th Birthday

- Between 4th & 6th Birthday

- Between 6th & 12th Birthday

- Between 12th & 18th Birthday

- Classification can be done by the medical professional. The family can also determine the classification using a family questionnaire. Better yet, the medical professional can collaborate with the parent to make the determination.

Other Research

The GMFCS has been used in multiple research into cerebral palsy. Here are some of the interesting findings in the past years:

- Hanna et al (2008) found a decline in function for children classified as Levels III-V starting at age 7 or 8 years old. Thus, it is important to minimize secondary impairments that may occur with age.

- Palisano et al (2010) described the probability of walking, wheeled mobility and assisted mobility among the 5 levels.

- Josenby et al (2011) found improved motor function, that also impacted GMFCS levels after dorsal rhizotomy.

Resources

- GMFCS website

- GMFCS descriptions and illustrations

Manual Ability Classification System (MACS)

The Basics

- The MACS describes how a child usually uses his/her hands to handle objects in the home, school, and community settings

- It includes 5 Levels:

- LEVEL I – Handles objects easily and successfully

- LEVEL II – Handles most objects but with somewhat reduced quality and/or speed of achievement

- LEVEL III – Handles objects with difficulty; needs help to prepare and/or modify activities

- LEVEL IV – Handles a limited selection of easily managed objects in adapted situations

- LEVEL V – Does not handle objects and has severely limited ability to perform even simple actions

- The instructions and distinctions among the levels are available here.

- Classifications can be done by a medical professional, educator, parent or child.

- You can also read SeekFreaks Article Review on the stability of the MACS.

Resources

- MACS website

- MACS level identification flowchart

- The Mini-MACS

- Validity and reliability of the MACS

Communication Function Classification System (CFCS)

The Basics

- The CFCS was initially developed to determine “everyday communication performance” of individuals with CP, as a complement to the GMFCS and the MACS. However, it is currently being used for individuals with any disabilities.

- The communication method considered in classifying the individual is not limited to speech. It includes any other means of communication such as sign language, gestures, facial expressions, augmentative communication devices, and others.

- It includes 5 Levels

- LEVEL I – Sends and receives information with familiar and unfamiliar partners effectively and efficiently

- LEVEL II – Sends and receives information with familiar and unfamiliar partners but may need extra time

- LEVEL III – Sends and receives information with familiar partners effectively, but not with unfamiliar partners

- LEVEL IV – Inconsistently sends and/or receives information even with familiar partners

- LEVEL V – Seldom effectively sends and receives information even with familiar partners

- The instructions, clarifications and level identification flowcharts are available here.

- Classification can be performed by a medical professional, educators, parents, caregivers and individuals with CP.

Resource

Eating and Drinking Ability Classification System (EDACS)

The Basics

- The EDACS was developed to determine eating and drinking of individuals with CP in everyday life.

- It includes 5 Levels

- LEVEL I – Eats and drinks safely and efficiently

- LEVEL II – Eats and drinks safely but with some limitations to efficiency

- LEVEL III – Eats and drinks with some limitations to safety; there maybe limitations to efficiency

- LEVEL IV – Eats and drinks with significant limitations to safety

- LEVEL V – Unable to eat or drink safely – tube feeding may be considered to provide nutrition

- The EDACS instructions may be downloaded from here. The algorithm is available here.

- Classification was shown to be reliable when performed by speech and language therapists and parents.

Resource

Visual Function Classification System (VFCS)

The Basics

- The VFCS was developed to classify visual abilities of children with CP. “Visual abilities refer to how the child uses vision purposefully to see, direct gaze, recognize, interact with the environment, and explore it…regardless of the body structure and functions underlying the visual disorder.” (Baranello et al, 2019)

- It includes 5 Levels

- LEVEL I – Uses visual function easily and successfully in vision-related activities

- LEVEL II – Uses visual function successfully but needs self-initiated compensatory strategies (such as head movements, eye-blinking, use of finger pointing, adjustment of the distance of the visual target, etc.)

- LEVEL III – Uses visual function but needs some adaptations (environmental modifications, adaptive equipment and technological devices)

- LEVEL IV – Uses visual function in very adapted environments but performs just part of visuion-related activities (and usually uses other sensory modalities such as hearing, touch, etc.)

- LEVEL V – Does not use visual function even in very adapted environments (has severe limitations in daily vision-related activities even if supported by significant adaptation uses almost exclusively other sensory modalities)

- The VFCS instructions for each level and for differentiating each level can be found here. Scroll down to “Supporting Information”, click on the dropdown arrow, then click on Appendices S2 and S3

- Classification was shown to be reliable when performed by health care professionals and parents.

Resource

Join Carlo Vialu and other experts at these all evidence-based, all practical continuing education courses:

November 6, 2023 at 9:58 pm

e34o4o