Written by Patti Sharp, OTD, OTR/L. Patti is a Certified CO-OP Instructor. She is an OT with 17 years of pediatric experience and works in outpatient at Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center (CCHMC). She previously worked in burns and neurorehabilitation, but now focuses on enhancing care in the developmental world. Patti has a contagious passion for evidence based practices which she imparts through the course, The CO-OP Approach and her Apply EBP webinars More information on these courses after the article below.

Do you ever have those moments in your OT, PT or SLP practice that shook up everything you thought you knew? One of my most impactful moments took place a few years ago.

Same Old Goals, Same Old Goals

I was (and am) a pediatric OT, working in an outpatient clinic of a large children’s hospital. I was seeing “Ellie,” a 7-year-old girl with “fine motor and sensory problems” per the referral. I had seen her for several 12-16-week episodes of OT over a few years. Scores on sensory processing assessments indicated several areas of difficulty and she continued to perform below the 15th percentile on standardized motor assessments as she aged.

Ellie was inattentive, clumsy, silly, kind of weak, and a little hypermobile. Sounds like one of your clients? She did “ok” in school and although her handwriting was far from neat, she no longer qualified for school services.

In years past, our goals circled around foundational sensory processing and motor skills, such as:

- improving body awareness,

- identifying a sensory diet to maximize attention and self-regulation,

- following instructions to complete motor skills without clumsiness, and

- using proper pencil grasp and letter formation for writing.

And of course, we would tack on age-appropriate functional goals that theoretically would be improved by working on those foundational skills – shoe-tying, handwriting, ball skills.

Ellie improved during every episode of therapy as measured by the Canadian Occupational Performance Measure (COPM) and as evidenced by general agreement between Mom and OT commenting,

- “wow, look at how much more fluidly she does that obstacle course!” and

- “she is definitely more regulated.”

The problem was that every few months when Ellie returned, I noticed that we were basically working on the same things. Sensory processing, coordination, fine motor control. It hit me one afternoon when I pulled up the goals set 6 months prior. The goals were noted to have been “met,” and I realized that I was about to set the same exact goals.

Why Am I and My Client Getting Stuck?

But why not work on the same goals? At the start of every episode of care with Ellie, I measured all these little components (sensory processing, coordination, fine motor control) and found that they are far different from the general population norms – they must mean that she is impaired! And if Ellie has impairments, she must have disabilities. And I could assume that her participation was negatively impacted, as well. Right?

And so it follows that interventions directed at those impairments would improve them, which would increase overall functional ability if we connected it to an age-appropriate functional goal, which would increase participation. Right?

This is basically the way I had been working with most of my clients – assess from the foundation and working my way up (aka bottom-up), treat from the bottom-up, and supposedly ultimately improve at the top.

But if this was correct, why was I getting stuck?

(For more discussions of each of these levels, see SeekFreaks’ “Recognizing ICF Words…Amusing Musings)

Why were Ellie and her mom returning month after month with the same goals? Why couldn’t I help her make lasting functional improvements? And did I ever really ask about her skills on a participation level?

Envision me coming to a screeching halt and freaking out – not just a little bit! The question slapped me in the face, are my interventions working? I mean, are they really helping to improve that child’s life?

I thought back through all my clients over the years. I knew they made measurable improvements, I knew their families were happy with what I was able to contribute and that they reported improvements as well.

But it kept nagging at me – why were these kids continuing to come back with basically the same goals over months and years?

Happenstance, Or How Continuing Education Helped Me

As chance had it, I had just attended a presentation about a condition called Developmental Coordination Disorder (DCD). The presenter described kids similar to Ellie, and a lot of my clients. They had vague or no diagnoses, those with “fine motor problems” or “poor coordination” or “clumsiness.”

The presenter explained that research showed that isolated motor tasks, like the activities measured by the Peabody Developmental Motor Scale (PDMS-2) or the Bruininks-Oseretsky Test of Motor Proficiency (BOT-2) generally don’t improve in these kids. If those activities are specifically worked on, they might improve, but there was no strong evidence that improving those component tasks would improve function. WHAT???

She explained that meaningful improvements in these kids can best be made by working on the goal tasks themselves…a top-down approach! Like if the child wants to tie shoes, the OT should start working directly on tying shoes.

Sounds obvious, right? But it’s not – or it wasn’t to me. In general, I spent a good chunk of my hour-long sessions on providing input to regulate attention and increase body awareness, and another chunk on “simulation” activities.

For example, if I wanted to facilitate a better pencil grasp, I had the child work on picking up small objects – using tongs or tweezers with varying size and resistance, stringing beads, putty, etc. And I would top the session off by having the child use the grasp that was (theoretically) facilitated by all the prior activities.

Now the Cartwheel that Was about to Change My Practice

So, sitting there with Ellie, I decided to switch gears completely. I had the list of things that Mom wanted to work on, which coincided with the things Ellie “should” be doing, which overlapped with prior therapy goals. I put the list aside and asked Ellie if there was anything she wished she could do better. “A cartwheel!” she said.

The presenter had briefly outlined an intervention approach called Cognitive Orientation to Daily Occupational Performance, or CO-OP for short. Using CO-OP, the therapist guided the child to independently come up with a self-articulated plan to accomplish a goal, then modified the plan based on performance.

With just the basic information on this intervention, I briefly described it to Ellie’s Mom and asked her if I could just try it for part of the session. She agreed.

Instead of assessing motor skills, bilateral coordination, or strength again, I just asked Ellie to show me her current cartwheel. It was cute and messy, and more like a bent-over hop-type-thing.

I asked Ellie to tell me how to do a cartwheel, and she was completely unable to elaborate beyond “well you just do this.” I took a video of her cartwheel on our iPad, then asked her to take a video of me doing a cartwheel.

We then sat down on a bean bag chair and I showed her the videos, back and forth. “Which one looks like the cartwheel you want to do? What is different about my cartwheel than yours?”

As instructed in the use of CO-OP, I tried to pose open-ended questions and allowed Ellie to come up with her own observations in her own language. Goodness, that was hard!

Typically, I would have instructed the cartwheel, after making sure Ellie was regulated and had worked on body awareness, bilateral coordination, and postural control. In this case, Ellie led.

“Your cartwheel is the right one! Your first hand matched your first foot. Mine was mixy.” Ummm…Yep…and she came up with that on her own???

“Your feet are in the air and the other one comes down before the first one.” Ummm… ok… maybe? I thought, well, might as well try it!

I prompted her to tell me her plan. “Starting foot, matching hand, legs up, other foot down first.” And then guess what happened? SHE DID A FREAKING CARTWHEEL.

Like a legit cartwheel. Messy, but correct! SHE JUST WHIPPED OUT A CARTWHEEL. Ellie danced around and kept cartwheeling while her Mom and I sat there speechless. I’m pretty sure I swore (oops!) and Mom said, “now how did you do that?”

I later returned to the office and did my best to not obsess over time spent on possibly less-effective interventions and promised myself I would begin to try this different approach. In subsequent sessions with Ellie, she made and modified plans to tie her shoes, ride a bike, and put her hair in a ponytail.

I let her play on the sensory equipment while I checked her in, but I let go of the formal input and obstacle courses. I let go of the preparatory or simulated tasks. Although Ellie was scheduled with me for 16 weekly visits, she met all of her goals in 5 sessions!

I reached out to her Mom a few months later, and she declined another episode of therapy, saying that Ellie was doing great figuring out how to do new things on her own.

Starting that day with Ellie, I gradually “flipped” my practice right side up. Ellie is unusual in the fact that she so rapidly and easily learned how to use strategies to learn and improve motor skills, but she is not unusual in her response to this “top-down” approach.

The Uncomfortable Change that Followed

Over the past few decades, therapeutic assessment and intervention were approached from the “bottom-up.” This means that we assess body structures and functions for impairments and that we believe that improving body structures and functions will decrease impairments and improve ability to do age-appropriate activities and participate in age-appropriate occupations.

Working from the bottom-up was a comfortable approach to myself and other therapists I know, perhaps, for these reasons:

- For one, it is widely used so it must be correct, right?!

- I can more easily measure impairments than participation.

- There are a decent amount of “therapeutic” things you can do in a 30- or 60-minute session that are aimed at reducing impairment – I have shelves full of equipment from tiny to large to prove that! It’s a comfortable way to move through a session.

“Top-down” approaches, on the other hand, are those directed at the goal activity or participation itself. Starting on this side was really uncomfortable to me for several reasons:

- It didn’t seem like other therapists were working from this angle, and I most definitely wasn’t a better OT than them.

- I think the most difficult part was that just working on the activity didn’t seem to need much expertise (or so it seemed).

- It felt much better to be able to assess components of a child (like sensory processing, motor coordination, range of motion, and strength), than just look at what the child wanted to do or needed to do but couldn’t or wouldn’t.

- It felt much smarter to confidently say that their measurably poor body awareness or inability to cross midline is the reason their child could not dress themselves or complete schoolwork without difficulty.

- It felt powerful to work on enjoyable things like prone mobility on a scooter and relate that to improved attention instead of trudging through difficult desktop work.

But I have to admit, there was a big part of me that felt like I was faking it. That I was assessing for all these little things, improving them, and then convincing parents that this would improve meaningful function and participation. And I really knew something was wrong when the patients kept returning with the same goals.

I did not jump into top-down 100% right away.

First, I slowly stopped using the beginning portions of my sessions to achieve “regulation” and instead went directly into working on goals. I used each session as a little test, knowing that I could always add preparatory activities back in if I felt they were needed.

I continued to offer fun sensory activities, no longer as skilled intervention, but now as reward, breaks, and rapport-building. I was shown session after session that lack of preparatory activity did not negatively impact the rest of my session and that I had much more time to work on the actual goals.

I also realized that it wasn’t the preparatory input that facilitated engagement, but instead allowing the child to be a partner in their intervention rather than a student of it. Having the child come up with their own plan to improve things that are important to them is astoundingly empowering.

The Literature Supporting the Top-Down Approach

A groundbreaking paper was just published by Iona Novak, an OT out of Australia. She completed a massive systematic review covering the massive scope of OT interventions for children with various disabilities (Novak & Honan, 2019).

The paper provided recommendations on which interventions pediatric OTs should continue to use, as well as others that should possibly be let go. Read SeekFreaks’ blog about this paper titled Traffic Light on Effectiveness of Various Pediatric OT Interventions by clicking here.

One of the main findings was a strong trend that effective interventions for children are top-down and occupation-based. The supported interventions are targeted at the participation and activity levels on the ICF, versus those that targeted at body structures and functions.

I have been gradually flipping my practice in this direction over the past 4 years or so, gathering my own experiential evidence supporting a bottom-up approach, but reading this landmark paper was so exciting and reassuring to me. Here are some more excerpts from research articles supporting the use of a top-down approach:

- Activity-oriented and participation-oriented approaches should be used as a means to improve general, fundamental, and specific motor skills (Blank, et al., 2019)

- Some interventions that aim to improve body functions and structures may be effective, but there is limited evidence whether they improve activity and participation (Blank, et al., 2019)

- The challenge for clinicians working with children with DCD should not be ‘how do I change motor skills?’ but ‘how do I support increased participation for this child?” (Allen & Casey, 2017) – shouldn’t this be true for all children and youth no matter the health condition?

Wondering what these evidence-supported top-down interventions (working on participation/activity levels) are? Here are some of them:

- Cognitive Orientation approach to daily Occupational Performance (CO-OP)

- Neuromotor Task Training

- Goal-Directed Training

- Handwriting Task Training (actual writing practice, not prep work)

- Context-focused Interventions

- Bimanual Therapy

- Constraint-Induced Movement Training

- Coaching

- Life Skills Training

- And more…

Visit the references below to find out more about these approaches.

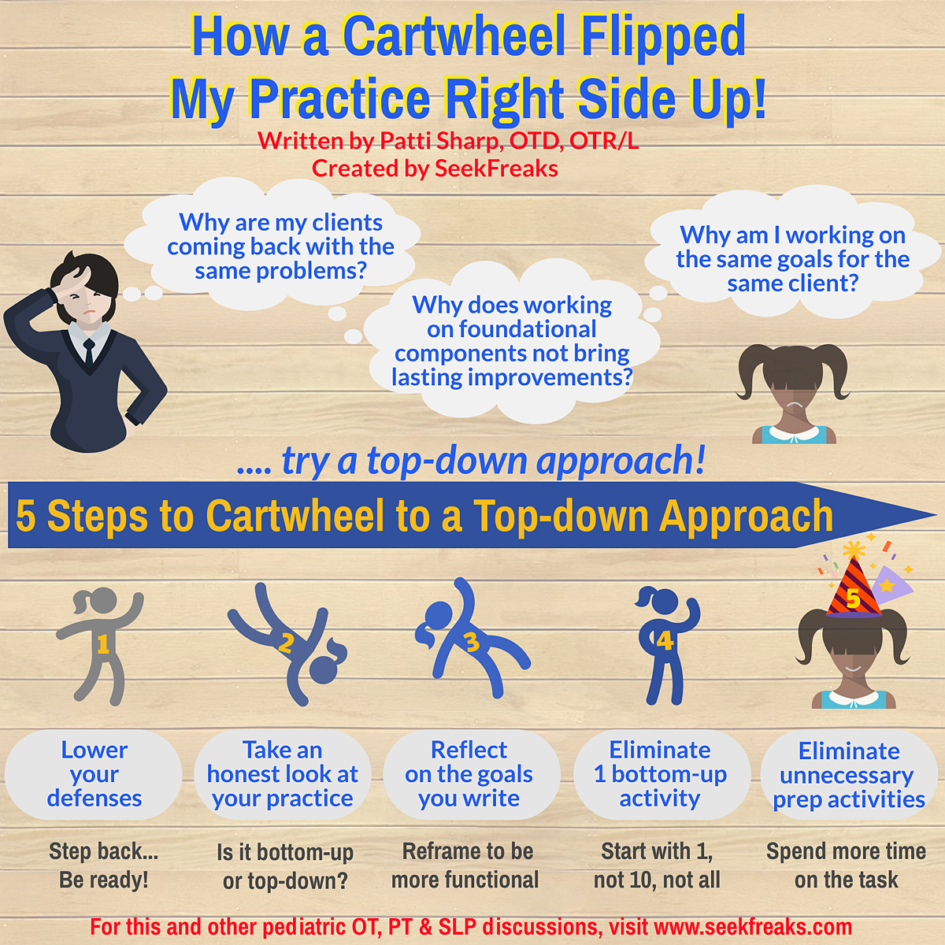

5 Steps to Cartwheel to a Top-down Approach

It’s hard to change gears, let alone perspectives. It is a process, and I will spell out how I flipped my practice. Try it for your own practice, and let us know here on SeekFreaks the challenges and successes you experienced along the way.

- Lowering my defenses

- Whenever I hear recommendations to change my comfortable ways, I knee-jerk into defensiveness. I’ll slightly bend the words of the recommendation and will put a spin on my practice, “of course I work on function and participation! Everything I do is functional and aimed at getting the child to do what they want, not what I want.” But when I take a step back, even now as I write this article, I can find some areas that are questionable.

- Taking an honest look at my practice

- What I did: I described this above with Ellie.

- Suggestion for you: Don’t criticize, don’t judge, just observe and ask, “am I working from the top-down or bottom-up?”

- Reflecting on the goals I write

- What I did: I really took a look at my charts and the goals. I had several goals that were something like, “will demonstrate improved hand strength for improved functional participation.” Functional participation in WHAT? I was taking shortcuts and not doing the work to define what skills were important to the child.

- Suggestion for you: Again, don’t criticize or judge, just observe. Ask yourself, “are these goals truly functional, or am I using them to eventually get to function?” If you find some body function/structure-based goals, try to change one of them to the functional activity you are ultimately trying to achieve. Just reframing the goal can help foster more functional intervention. Remind yourself that you can always change the goal back. Then see what happens.

- Eliminating a single bottom-up activity

- What I did: I started with letting go of putty and tongs.

- Suggestion for you: Just choose one, not 10, not all! Once you identify that one thing, stop doing it. Remind yourself you can always go back to it if needed. Then see what happens.

- Eliminating unnecessary preparatory activities

- What I did: I noticed that prep activities consumed a large portion of my session. I need more time to practice the actual task the child wants to work on, so I let go of all prep activities. I stopped doing obstacle courses (as intervention) – you know how much time it takes to ready the course, then to go through the course a few times, and finally clean up the course!

- Suggestion for you: Do you notice how much time you spend on prep? Your clients may be more “prepared” to engage with you than you think. Try to let some of that go, as well. Stop, know you can always add it back in. Then see what happens.

Remember, evidence-based practice is the intersection of patient preferences, research, and clinical experience. Ellie told me her preference to learn a cartwheel, the presenter of the continuing education I attended showed me research to support a top-down approach, then it was up to me to try changing my practice and gather my own evidence via clinical experience.

Take a chance…do a cartwheel for your own practice…you might be absolutely blown away like I was.

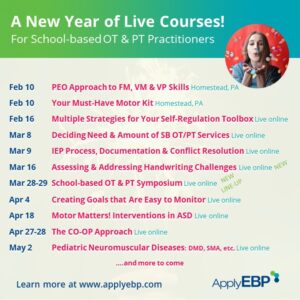

Catch the author, Patti in the following Apply EBP courses and webinars

September 13, 2019 at 9:17 pm

Patti, thank you! I will use this blog for required reading for my grad OT students; terrific explanation of top-down and CO-OP that dovetails nicely with the ICF/OTPF3 levels for intervention we go over in class! Again, many thanks!

September 14, 2019 at 1:05 pm

Thank YOU, Peggy – your fabulous review of Novak’s systematic review gave me the push I needed to write it. I’m encouraging all my colleagues to read your post and gather the courage to change some yellow and red-light practices. Thank you!

November 28, 2020 at 5:24 am

Dear colleagues,

Congratulations on an excellent article! I just came across by chance and it is such a great journey, similar to my own as an OT.

My practice has been aligned in the same way to yours for some time now, but finding it hard to communicate this to the schools I work with, since educational professionals believe in bottom up approaches.

I’m putting together some training to address these gaps, and would like to seek your permission to use your bottom up vs top down approach image in one of my slides, since it summarises things so well. Do let me know if you have any issues with this request.

I will be tweeting your article to all my channels (I have influence here in the UK as social media officer for our CYPF specialist section), as I feel is such a great resource.

Kindest regards,

Patricia.

May 7, 2021 at 8:44 am

So well written Patti and so inspiring!

Thank you so much!

I just refered to it at the ICAN COOP LinkedIn page: https://www.linkedin.com/in/ican-co-op-approach-38796b210/

best wishes! Jolien van den Houten

November 6, 2023 at 9:58 pm

eyhaig