Written by Peggy Morris, OTD, OTR/L, BCP . Peggy is an OT with 30+ years

pediatric experience in early intervention, private practice, and out-patient services – but most of her experience and passion is in school-based practice. She teaches graduate students in the occupational therapy department at Tufts University, and man, do they keep her on her toes! She practices yoga, garden, and play golf for mental health and wellness. Catch Peggy and her colleagues in…

[smbtoolbar]

Coaching as a way to deliver client-centered school-based therapy services. What?! While I am not quite a pom-pom kind of person, I do enjoy being a cheerleader for my clients. I also like telling people what to do! And that is so not the purpose of coaching. (By the way, SeekFreaks, here I use the term “client” to refer to the student, the family, teachers, or others we worked with to help our students reach their IEP goals.)

Why Coach?

One of the key purposes of coaching is to increase the knowledge, skills, and competencies of a client to enable participation in the context of daily life. This is an enablement model, a competency-building model, and can support a strengths-based practice.

Let me introduce you to one study (Kientz & Dunn, 2012) that used coaching as the intervention model to empower and enable eight boys (ages 11-17) with a diagnosis of ASD to meet their goals and then we can talk more about how coaching may fit into schools practice.

This study’s authors partnered with each of these adolescent boys and at least one parent each and utilized a coaching model that supported these young men to make their own goals, problem-solve, analyze the situation in context, and determine a plan of action/solution. This is the tough part: the therapists using this model (with training) did not offer suggestions or advice or accommodations or remediation activities; this is a model that requires the therapist to be able to ask reflective questions and participate in reflective discussion so as to facilitate the client choosing their own goal and direction to meet that goal.

I know. I know. I LOVE having a positive impact by problem-solving my way through to a unique solution and sharing with a family or a teacher. I LOVE being the creative solution-maker that people thank me for. (If we are honest with ourselves, we receive a lot of personal satisfaction when we are recognized as the problem-solver for others; we’re built that way!)

In this coaching model, we have to let go of telling other people what to do….oh, boy! That is really hard for me to do. But something else in this study sold me on this model, as one that provides contextual services and honors our students, families, and teachers as drivers of the intervention process.

In this study, the adolescents and their parent teams made goals in ADL areas (brushing teeth, dressing, bathing), IADL goals (cooking, sleeping, grocery shopping, phone use), and leisure goals. After eight, yup, you heard that right, 8 hour-long sessions of intervention, progress towards goals was significant on the Canadian Occupational Performance Measure (COPM) at a p < .001 level for both performance and satisfaction, and on Goal Attainment Scaling (GAS) at the p < .001 level of significance.

That p level of < .001 is a statistic that researchers dream about! Those kind of statistical numbers, through ANOVA (pre-test, post-test, delayed post-test) and paired t-tests make me sit up and take notice, especially since the COPM and GAS are well-known as outcomes measures, and for their sensitivity to progress and change. And, especially since the areas of change are in important functional life skills.

I’m sold! I know the ‘n’ in this study is a small one, only 10 boys participated. But this is just one of about 11 studies to date on coaching in occupational therapy; it is a newer model for intervention and the evidence is emerging as weak, but positive.

That’s the thing about evidence-based practice: the best evidence available may not be clean, well-designed, thorough random-controlled trials (RCTs) and that’s OK. We can’t wait for better evidence to be produced; we evaluate the best evidence that is current at the time we are working with our clients.

The Coaching Process

So, since I’m sold, I’ve looked for descriptions of what this coaching process actually looks like. In the Kientz and Dunn study (2012), they followed Rush & Sheldon’s (2011) model for coaching with five key elements of joint planning, observation, action, reflection, and feedback.

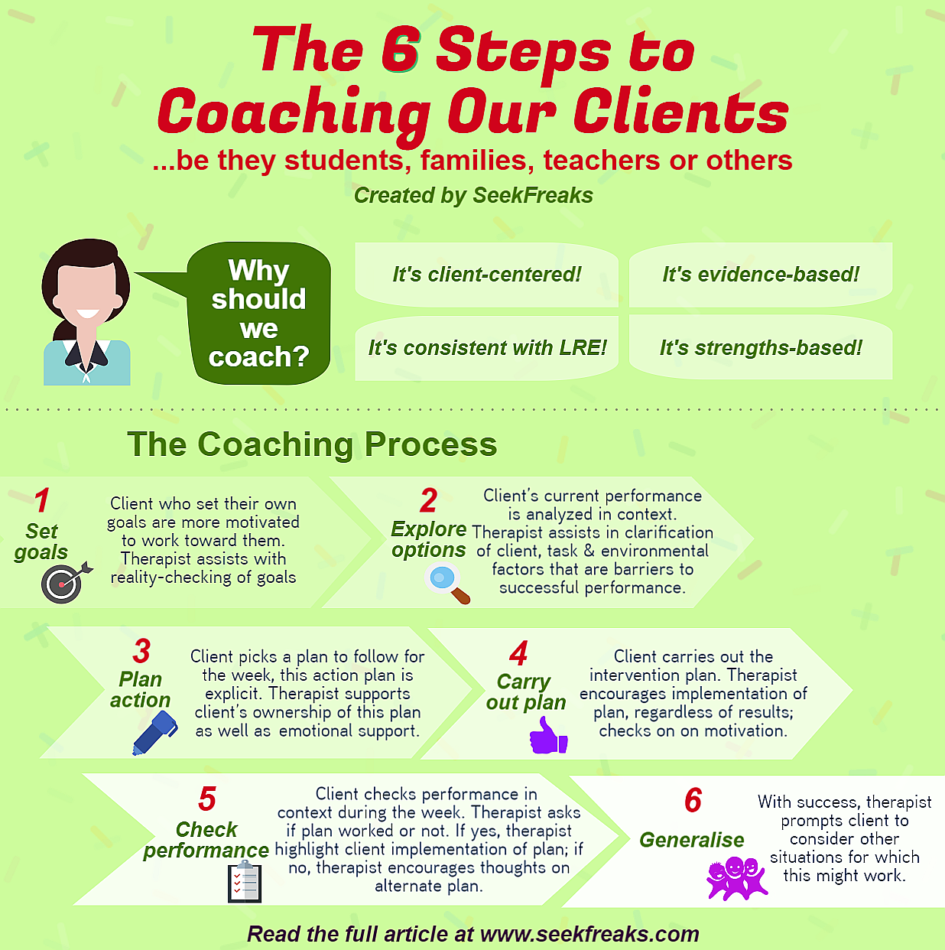

Another research team in this area, Graham, Rodger, and Ziviani, has produced at least three papers in this area, using the term occupational performance coaching (OPC). They describe their coaching process as “a structured process of: (1) setting goals, (2) exploring options, (3) planning action, (4) carrying out the plans, (5) checking performance, and (6) generalising” (p. 211 in Graham, Rodger, and Kennedy-Behr, 2017).

- Setting Goals: Client who set their own goals are more motivated to work toward them. Therapist here assists with reality-checking of goals

- Exploring Options: Client’s current performance is analyzed in context. Therapist assists in clarification of client factors, task factors, and environmental factors that are barriers to successful performance, taking care to honor client perspective in this process.

- Planning Action: Client picks a plan to follow for the week, this action plan is explicit. Therapist supports client’s ownership of this plan as well as emotional support.

- Carrying Out the Plans: Client carries out the intervention plan. Therapist encourages implementation of plan, regardless of results. Checks on on motivation.

- Checking Performance: Client checks their performance in context during the week, given this implementation. Therapist asks if worked or not. If it worked, therapist intentionally highlights client implementation of plan with performance over the week. If not successful, therapist encourages thoughts on alternate plan.

- Generalising: With success, therapist prompts client to consider other situations for which this might work. There may be many loops in planning action/carry out action/check performance before we get to generalising.

As I boil it down for me, this intervention approach uses a conversational format that is goal-focused and relies heavily on the practitioner’s ability to provide reflective prompts rather than provide answers, so that, in the end, the clients, whether they are parents, students themselves, or teachers drive the intervention process. Improved occupational performance is facilitated when a better match between and among the person, the environment, and the occupation (PEO) is achieved.

Aditional Benefits of the Coaching Model

In the literature available outside of the Kientz & Dunn (2012) study, several more smallish studies (n = 3 to 29) have used this model of intervention (Dunn et al, 2012; Foster et al, 2013; Graham et al, 2013, 2010, 2009; Kennedy-Behr et al, 2013; Kessler & Graham, 2015). Three things float my boat!

- The first is how this model aligns with client-centered and contextual intervention. I am all over contextual intervention, so addressing issues where and when they are happening, not necessarily in the pull-out OT or PT space. And there is some solid evidence out there that contextual interventions get students to goals just as equally as non-contextual interventions. Here is one SeekFreaks article review on a context- versus child-focused intervention models for you to consider.

- The second Wowser! moment comes from several of these studies that suggest parental sense of competency, efficacy, and satisfaction are improved within this model (Dunn et al, 2012; Graham et al, 2013; Foster et al, 2013). To me, this sits nicely with family-centered/client-centered practice.

- The third piece that REALLY floats my boat is that this has been tried in schools practice (Kennedy-Behr et al, 2013)!!!. Yahoo! Let me describe this study.

- Three preschool teacher-student dyads were involved (yup, a small n) and the focus of intervention was to assist the preschool teachers to set goal(s) for their particular student and then facilitated to analyze what the environmental barriers in their classrooms might be for this child’s successful participation.

- Over 4 weeks (once weekly) teachers and the occupational therapist met for 15-30 minutes; the OT facilitated the teacher to set an action related to the goal she had set for her student and then followed up on what worked/what didn’t work at the next meeting.

- Again the COPM was used, and seven of the nine goals set (3 for each child) for student performance demonstrated change equal to or greater than two points, which is considered to be clinically significant (Law et al, 2005). And get out! The teachers’ satisfaction regarding the student’s performance also improved by two or more points in seven of those nine goals. In FOUR weeks!

I know some folks might worry that we are giving away our power as related service providers if we teach others how to think about intervention. Some folks have even talked to me about the possibility of losing their job if we give away our secrets.

While I understand this worry, I truly think that this type of practice honors an empowerment model for our pediatric clients and the adults in their lives. I think children with needs will always be there for us to work with; I see this as just a different way to spend my therapy time with them. I have moved my thinking to “What do my clients need right now?” and “How can they think for themselves about this problem?”

Exciting information for you? I hope so! The preschool teachers in the Kennedy-Behr et al study (2013) found that the new knowledge they gained could actually be transferred to other children in their classrooms. The idea that we can address a knowledge gap by using this coaching model heads us toward a more inclusive educational model, a more transparent model, and what looks like promising outcomes in these studies of this emerging practice.

Are you thinking about how this may apply to your practice? If so, here is a place to start. Ask questions rather than answer questions!!! Here’s an example that is probably familiar:

Charlotte (teacher): “Peggy, Sammy’s become quite explosive in social situations, especially at snack time. What should I do?”

Peggy’s response before understanding and trying coaching: “Sure, I can come to snack time. It’s probably something sensory and I can figure out a couple for suggestions for you.”

Peggy’s response after understanding the evidence on OPC: “Charlotte, can you describe what is going on for Sammy at snack time?”, then perhaps “What have you tried already?”, then perhaps “Did it work?”, then perhaps “What do you think about that?” then perhaps “What else might you like to try?” It’s a skill I needed to cultivate and a habit I wanted to change; I’m still developing competencies in this area.

Hmmmm…continued professional development, even after 30+ years in the field. That’s an evidence-based practitioner!

Catch Peggy and other evidence-based presenters at…

References

Dunn, W., Cox, J., Foster, L., Mische-Lawson, L., & Tanquary, J. (2012). Impact of a contextual intervention on child par- ticipation and parent competence among children with autism spectrum disorders: A pretest–posttest repeated-measures design. American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 66, 520–528. http://dx.doi.org/10.5014/ajot.2012.004119

Foster, L., Dunn, W., & Lawson, L.M. (2013). Coaching mothers of children with autism: A qualitative study for occupational therapy practice. Physical & Occupational Therapy in Pediatrics, 33(2), 253-263.

Graham, F., Rodger, S., & Kennedy-Behr, A. (2017) in Rodger, S & Kennedy-Behr, A. (Eds.) Occupation-centred practice with children. UK: Wiley-Blackwell.

Graham, F. Rodger, S., & Ziviani, J, (2013). Effectiveness of occupational performance coaching in improving children’s and mothers’ performance and mothers’ self-competence. American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 67, 10-18.

Graham, F. Rodger, S., & Ziviani, J, (2010). Enabling occupational performance of children through coaching parents: Three case reports. Physical and Occupational Therapy in Pediatrics, 30(1), 4-14.

Graham, F. Rodger, S., & Ziviani, J, (2009). Coachiang parents to enable children’s participation: An approach for working with parents and their children. Australian Occupational Therapy Journal, 56, 16-23.

Kennedy-Behr, A. Rodger, S., Graham, F., & Mickan, S. (2013). Creating enabling environments at preschool for children with developmental coordination disorder. Journal of Occupational Therapy, Schools, & Early Intervention, 6, 301-313.

Kessler, D. & Graham, F. (2015). The use of coaching in occupational therapy: An integrative review. Australian Occupational Therapy Journal, 62, 160-176.

Kientz, M & Dunn, W.(2012). Evaluating the Effectiveness of Contextual Intervention for Adolescents with Autism Spectrum Disorders. Journal of Occupational Therapy, Schools, & Early Intervention, 5:3-4, 196-208, DOI: 10.1080/19411243.2012.737271

Law, M., Baptiste, S., Carswell, A., McColl, M., Polatajko, H., & Pollock, N. (2005). Canadian Occupational Performance Measure (4th ed.). Ottawa, CN: CAOT Publicatons ACE