Written by Peggy Morris, OTD, OTR/L, BCP . Peggy is an OT with 30+ years

pediatric experience in early intervention, private practice, and out-patient services – but most of her experience and passion is in school-based practice. She teaches graduate students in the occupational therapy department at Tufts University, and man, do they keep her on her toes! She practices yoga, garden, and play golf for mental health and wellness. She presents evidence-based courses via Apply EBP webinars. More information on these symposiums after the article below.

Pandemic Funk

I am coming out of my pandemic funk. Not out of physical isolation, not out of Zooming to work; but gently, slowly recouping from the cascade of deep emotions layered with fatigue. I recall the moment for my 180-degree turn-around, from “WTFreak” to “Ok, I got this, not easy but I got this.”

It happened last month, early one afternoon, after I was guest-lecture Zooming on a topic about which I am jazzed, passionate. Then I remembered my digging around into the research in positive psychology and recalled clearly that positive emotions can help to dissipate negative ones. My 180 actually happened that way.

Everyone is on a different path in terms of the tax on their executive functions, processing new information, wearing multiple hats simultaneously; there is actually Zoom fatigue…it is a Thing! And every path is authentic. My path is levelling off, I am a little clearer and more self-regulated, I have doubled up on my mindfulness minutes. And I am back to reading.

I had downloaded many of the articles from the March/April 2020 volume of the American Journal of Occupational Therapy, when it was first available, put them in one of the MANY folders on my desktop, and promptly forgot them. This is not unusual; it is generally how I store new research articles until I can get to reading them.

The Perfect Storm

Perfect storm: I am coming out of my funk and Carlo Vialu texts me: “Peggy, have you read Grajo et al, 2020 yet?” P: “Nope, I have not. Is it from the newest AJOT?” C: “Yup! Go read it!”

He knows me well! Grajo et al, 2020 is indeed in the folder on my desktop marked 2020 Sys Revs, which is my shorthand for systematic reviews. This volume of AJOT, focusing on children and youth, actually includes 8 systematic reviews, one scoping review, a guest editorial on becoming critical consumers of evidence for pediatric therapists, AND…a replication study of two-often-cited studies (McHale & Cermak, 1992 and Marr et al, 2003) in the area of fine motor demands in elementary schools. This is an evidence bonanza! Holy crow, I am all in. Systematic reviews are like my chocolate now!!

I started with the guest editorial, which is Open Access; you can read it even if you are not an AOTA member. The guest editors (two of whom I professionally stalk at conferences) talk about how much more research is available within the scope of pediatric occupational therapy, as well as the assumption that once published, it is easily accessible and understandable. And that is an assumption…we know it is typically challenging to translate the research into practice changes.

AOTA and committed volunteers have devoted resources to developing the Evidence-Based Practice (EBP) Project. Just troll around this AJOT volume or the AOTA site and you can see the evidence of the EBP project. Sorry, just had to do that language!

One of the ways to overcome the challenge of research translation into practice is the systematic review. This type of research gathers all pertinent studies in a very formal way and summarizes the strength and practical implications of the evidence. I have always said that authors of systematic review do all the heavy lifting for us. We just have to head in and read them. The truly heavy lifting for us as clinicians is to decide if we are ready to make changes in our practice if the evidence leads us to think this way.

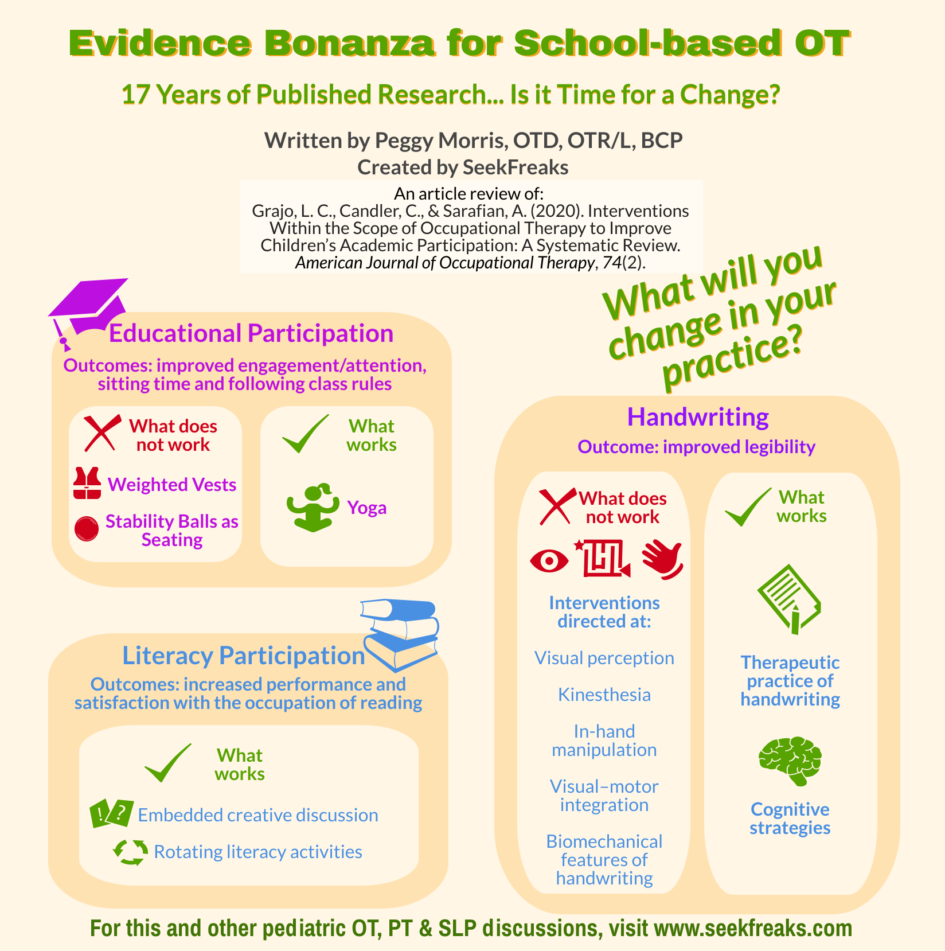

Effective Interventions for Successful Academic Participation

Next up for reading: the Grajo, Candler, & Sarafian 2020 systematic review of interventions within the scope of OT to improve children’s academic participation (full citation is below; also Open Access). This is a good must-read for all school-based therapists, when you have the brain space to do so. I can summarize the summaries.

These authors developed a question by which to determine if a research study should be included in this systematic review. Their question: What is the evidence for the effectiveness of interventions within the scope of occupational therapy practice to improve learning, academic achievement, and successful participation in school for children and youth ages 5–21?

They also developed inclusion and exclusion criteria, which all systematic review authors do, and described their use of the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (2018) guidelines for assessing strength of evidence as Strong, Moderate, or Low. One of their inclusion criteria was that the study had to be at the Level I, II, or III, of evidence, so no case studies or expert opinion pieces. They also operationalized three themes for study outcomes:

- Educational Participation

- Literacy Participation, and

- Handwriting

Let’s talk about them one at a time.

Effective Interventions for Educational Participation

The area of Educational Participation was defined by outcomes such as:

- classroom on-task behaviors

- engagement and attention

- ability to follow classroom rules

- academic performance

- amount of time spent sitting to attend to classroom tasks

- other outcomes

Three types of interventions were described in the research studies:

- weighted vests

- stability balls

- yoga

Weighted Vests

Weighted vests for children with ASD (this was the population in the studies that met the inclusion criteria) to improve academic participation is low, indicating insufficient evidence to support use of weighted vests for children on the spectrum.

This systematic review supports the 2016 AOTA Practice Guidelines for Individuals with Autism Spectrum Disorder recommendation for not using weighted vests as intervention. Practically-speaking, the implementation of this recommendation is to not use weighted vests for children on the spectrum for improvements in educational participation (increased sitting time, increased attention, increased ability to follow classroom rules). This systematic review states these types of behaviors did not significantly improve.

Stability Balls

The same is true for stability balls: low evidence for use as an intervention to increase time on task or better math and literacy outcomes. The implementation of this systematic review would be to not use stability balls to increase attention, time on task, or academic performance. Note here: use of stability balls for therapeutic outcomes is different than use of a variety of seating/standing items for flexible seating options in a Universal Design for Learning (UDL) framework.

Yoga

Yoga research demonstrated moderate evidence to enhance school participation, particularly attention, social interaction, and on-task performance as rated by teachers. If you are trying to improve paying attention and on-task behavior in the classroom, the implementation of this systematic review is yoga over weighted vests and stability balls as the practical advice.

Effective Interventions for Literacy Participation

The second theme for this systematic review relates to outcomes in the area of Literacy Participation. Participation in literacy activities is at the heart of educational participation.

While school-based occupational therapists’ role is narrowly perceived more in the handwriting aspect of literacy, participation in the whole of literacy activities is the focus of this theme, and can be supported by school-based occupational therapists (AOTA, 2014).

There is strong evidence for the use of the following to support increased performance and satisfaction with the occupation of reading.

- Embedded creative discussion and

- Rotating literacy activities

When I read this, I was reminded of being in the kindergarten classroom with three students with whom I was working (embedded), engaging with them in the story of the week (Anansi and the Moss-Covered Rock), and manning an educational station where we made Anansi and other characters from the book from found materials.

My role was to model for the students I was working with, as well as any others who were at the station, how to sequence the Anansi spider (or moss-covered rock, or bananas) we were making. I also adapted the painting tools and graded the activity on the fly when necessary. All in the long-term service of making props for the eventual class play, based on the Anansi story.

As you work to implement this part of the systematic review for academic participation outcomes, practically-speaking, it supports the occupational therapist being embedded in the classroom, during literacy activities to support participation in the literacy activities, using our unique lens to adapt materials and grade the activity. Strong evidence.

Effective Interventions for Handwriting

The third theme of the included studies is Handwriting. this area had the majority of studies in the systematic review. Reading this systematic review validated what I have been reading in the research to date: no studies provide support for addressing the component skills assumed to underpin intervention for handwriting legibility outcomes.

Four recent RCTs, so studies with strong methodology and low risk of bias, identify that working on visual perception, motor skill and or kinesthesia does not improve handwriting legibility.

The practical application of this systematic review finding is to not work on the isolated components with visual perception activities, motor skill activities, or kinesthetic activities if your student outcome is for increased legibility of handwriting.

Aside from these 4 RCTs, other Level 1 studies describe interventions that do increase handwriting legibility:

Strong evidence exists for:

- Therapeutic practice of handwriting, which includes pencil-and-paper practice of handwriting

- Cognitive strategies, such as self-evaluation

This strong evidence supports therapeutic practice over sensorimotor approaches (the component activities of visual perception, kinesthesia, in-hand manipulation, visual-motor integration, and biomechanical features of handwriting).

We have the dynamic duo of intervention evidence for handwriting intervention: a series of studies that identifies what does not work and another series of studies that identifies what does work.

In the service of practical application, if you are working with a student on an outcome for improved handwriting legibility, practice writing words, and not on using visual perception worksheets or fine motor activities.

This practical application is considered evidence-based practice based on 17 years of research (2000-2017); yet we are used to working on the component areas to support handwriting improvement as school-based therapists. Remarkably, 17 years is about the time that research recommendations makes it into practice! (Morris et al, 2011; Thomas & Law, 2013) Go figure!

Maybe, just maybe, it is actually time for an elected change, a change we choose. This pandemic has forced change on us. It has forced tele-education and tele-health, forced tele-socializing, and forced tele-related services, with generally little to no training and support. Force is an F-word I do not like. Forcing change can certainly bias us against thinking about change as positive, for sure.

I am heading back into my positive psychology frame of reference. I want to choose my next change. Can you envision a change, based on evidence, for when work returns to some kind of new normal? If you are at all interested in using this systematic review to support a change in your practice, yahoo! If you are challenged to use this research to change your practice, reflect about why.

When we are ready for change, how do we change our thinking and working habits? My first step was changing how I evaluate when I receive a handwriting referral. I used to start with a common test of visual motor integration, but when the evidence indicated that scores on this assessment tool were not related to increased legibility, I stopped administering it for a handwriting referral.

Because I stopped using this test, I had carved out some time in my evaluation process and was able to add application of the legibility formula (Case-Smith et al, 2015) to assess student handwriting samples. Hocking (2001) wrote how we evaluate determines how we intervene.

Makes sense that if we administer a visual motor integration assessment tool, we will intervene with visual motor activities. Same for visual perception. If we administer a visual perceptual standardized assessment tool, we will likely develop and use visual perceptual activities in intervention. Practically speaking, these tools don’t give us the information we truly need in order to design handwriting intervention that is evidence-based.

Practically speaking, if you’re ready, choose not to administer these types of tools for your next handwriting referral. What?! Rather, choose to calculate the legibility percentage on several samples; if the word legibility is below average, then your handwriting remediation will focus on handwriting practice for improved legibility.

Changing your clinical reasoning for using specific assessment tools will impact your intervention choices. This is one place where we can control the change we strive for as the evidence in our field continues to expand.

What will you change in your practice?

When our world returns to a new normal, it looks like new routines will be a part of that re-opening. Maybe this is just the time, even though it is a catastrophic time, for a chosen change. Seventeen years of research is a good foundation for planning a clinical change.

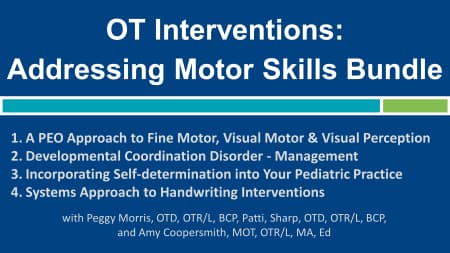

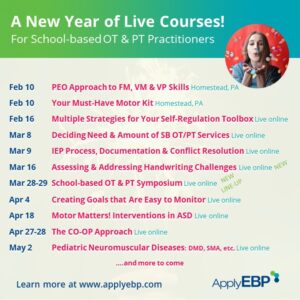

Join Peggy and other evidence-based presenter at these webinars

References

American Occupational Therapy Association. (2014). Occupational therapy practice framework: Domain and process (3rd ed) American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 68 (Suppl 1), S1– S48, http://dx doi org/105014/ajot 2014 682006

Case-Smith, J. & O’Brien, J. (2015). Occupational Therapy for Children and Adoelscents, 7th ed. St. Louis, MO: Elsevier.

Grajo, L. C., Candler, C., & Sarafian, A. (2020). Interventions Within the Scope of Occupational Therapy to Improve Children’s Academic Participation: A Systematic Review. American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 74(2).

Hocking, C. (2001). The Issue Is: Implementing occupation-based assessment. American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 55, 463-469.

Marr, D., & Cermak, S. (2003). Consistency of handwriting in early elementary students. American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 57(2), 161-167.

McHale, K., & Cermak, S. A. (1992). Fine motor activities in elementary school: Preliminary findings and provisional implications for children with fine motor problems. American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 46(10), 898-903.

August 19, 2020 at 8:19 pm

Thank you for the review. Great information. I love this website.

February 4, 2023 at 4:37 pm

I’m new to school based OT and would appreciate any info/resources for legibility formula/percentages with regards to assessing legibility of handwriting.

Thank you!

November 6, 2023 at 9:59 pm

u81ml9